MsC 746

THE MARION BALLOU FISK PAPERS

Collection Dates: [1906 -- 1930]

.5 linear ft.

Scans of a document from a collection of materials

held by the

Special Collections Department

University of Iowa Libraries

Iowa City, Iowa 52242-1420

Phone: 319-335-5921

Fax: 319-335-5900

e-mail: lib-spec@uiowa.edu

To inventory

of the Fisk Papers

Mrs. Fisk’s daughter, Marion

Fisk Giersbach, typed her mother’s program source material below. Unfortunately, Mrs. Fisk’s original

handwritten “script” of her lectures doesn’t exist. As you read her description of people and

places, you can imagine her drawing a quick sketch on her easel, then turning

to the second easel for another scene before returning to the first and

continuing with a fresh sheet of paper.

KWEER

KARACTERS I’VE KNOWN

It is an old story that I presume is a familiar one

to all of you, about the old couple who sat talking together one evening. One by one they held up their relations and

friends for ridicule or criticism, until at last the old lady closed the conversation

by say, “Yes, Ezry, all the world is queer but thee and me – and, do you know,

sometimes it strikes me that even thee is a little peculiar.”

So it is with us here tonight, “all the world is queer

but thee and me.” Indeed I do not doubt

that if I could stay in ..... long enough, I might even find some queer characters

here, and I know very well that you have come to see and hear a queer woman

talk and draw pictures, and so to divert your attention from myself for a

little while, I want to introduce you to some of the other KWEER KARACTERS

I have known.

Before

proceeding, however, further with the program, it may not be out of place

for me to introduce myself to you a little bot more fully than has even yet

been done.

A

great many people ask me questions about myself as I go from place to place.

The one that is most frequently asked is this, “How in the world do

you get your hands clean.”

I

don’t

A

close second is this: “Now, this ability of yours to draw pictures – is it

a natural gift or an acquired one?”

I think that I may safely claim that whatever gift I

have in this direction is a natural one, for it is one that is shared in common

with all my family. My father draws

– a pension. My mother draws – books

out of the public library, and my brother draws – a salary. Again, I think I may claim that it is a natural

gift, for it is one that I have always possessed. Indeed my parents tell me that I may safely

make the claim to have been a precocious child, for they assure me that the

very first thing I ever did after my birth was to begin to draw – my breath.

I was very young, I think not over three years of age, when I can distinctly

remember drawing a little blue sled – by the string, and it was about this

time that I attempted to draw our family cat – by the tail.

I think, however, this might more properly be classed as a painting,

for I bore the marks of that brush for some time, and the cat proved herself

the better artist of the two, for she drew blood.

But speaking more seriously, I still think that I may

safely claim that whatever gift I have is a natural one, – one that was bequeathed

to me by the best friends and playmates of my childhood, the mountains and

hills, the lakes and the clear little streams, the lights and shades of my

own New England home. And so tonight

I want to take you away for a little while, if I may, to this land of my nativity.

It is a trip that is well worth taking, too, and one

that many people do take each year, at great pains and expense, for this little

town that first sheltered my childhood is rich, not only in natural scenery,

but in historic interest, as well, for it is one of the seven little towns

that was so long bandied back and forth, like a bone of contention, between

the rival territories of New York and New Hampshire, until at last these seven

little towns decided that if they were indeed so valuable, and so much to

be desired, they were quite capable of managing their own affairs, so a rebellion

sprang up – a teapot rebellion, if you choose to call it so, – a few shots

were fired, a little blood was shed, and so Vermont was born.

If I could take you into the town in the way that would

please me best, we should leave the beaten line of travel some distance below

the village and make our way, on foot, across Hurricane Hill. Then, as you come to the brow of the hill, if

you have an eye for the beautiful, I know you would pause to admire the scene

spread out before you. Far away, against

the horizon, marches the great bulk of the Green Mountains, with the lesser foothills

near by.

Just opposite you stands William’s Hill. Probably no curiosity would prompt you to ask

the reason for it, or even to inquire as to how it came to bear that name,

for you would assume as most people do, that a family by the name of Williams

owned it in the early days, but that is not the case, and by the name of William’s

Hill and how it came to bear that name hangs one of the oldest old New England

traditions.

It is one of the stories that used to be told frequently

a hundred years ago when people gathered together for an evening and told

stories around their fireplaces. It

dates back to the time when the country was very new; when people lived in

log houses and the fires were never allowed to go out on the hearthstones,

by day or night, for matches were a thing unknown, and if, by any evil chance

such a calamity did occur, then the swiftest runner of the family was dispatched

with all haste, with a covered bucket, or a fire shovel, to borrow coals from

the nearest neighbor, for the next kindling; to the time when women laid their

hands to the distaff, and spun and wove, and looked well to the way of their

households, nor dreamed of the Tango or Turkey Trot. When they rode to church Sunday mornings, on

pillions, behind their men folk, clasping fast the great family Bible, while

the husband carried the gun, for the bear and the wolf were frequently seen,

and the Indian was a constant menace.

It appears that in those days there was one young William

Jones, who fell violently in love with Mary Green. Mary Green appears to have been a young woman

of unusual beauty and promise, and after one of those long, drawn out, old-fashioned

New England courtships, the couple became engaged to be married.

One winter night, as they were making their way home

over the snow-covered hills, in company with a party of friends from a merry

making of some kind, they were startled by the hungry cry of a wold pack far

in their rear. It was answered away

at the left, then at the right, and then far away in front of them. At last the young people realized with a sickening

sense of fear that the hunger cry of that wolf pack was meant for them, so

they made all haste to a great tree that stood in a field hard by, and climbed

to safety and protection in its broad branches. Thither, presently, came the wolves, and gathered

about beneath the tree, looking up at the would-be victims with gleaming eyes

and slathering tongues. But the young

people sat, perched high and in safety, and so the long hours of the night

wore away, until at last beautiful Mary, having grown weak from nervousness

or chilled with the cold, lost her hold, and fell to the ground beneath.

This story has been woven into one of those old, old

fashioned songs that used to frequently be sung a hundred years ago, but which

are almost unknown and obsolete now, but which, it seems to me, should be

preserved, not only as something of a literary curiosity, but from a historical

interest as well, for so many of those old songs give us a unique but vivid

picture of conditions as they used to be when our country was new, and its

customs still in the making. It was

one of those old-fashioned minor melodies with a refrain that was a conglomeration

of meaningless words and phrases and syllables, and began in this way.

“Come all ye people, high and low,

And you shall hear if [of?] a dismal go.

It’s all about one little Mary Green

She’s the prettiest little girl that ever was seen.”

I’m not going to sing any more of them, but there are

thirty-nine more verses to that song, and they go one to explain the virtue

and beauty of Mary, the strength and valor of William, and the great Love

they bore for one another, and Mary’s tragic fate.

They appear to have taken love very seriously in those days, and when

either a lover or a sweetheart were lost, the one who remained behind proceeded

to “mourn themselves to death, and be buried in one tomb.” I don’t know, I am sure, what they would think

of these days of rapid-fire marriages, with automatic divorce attachments.

Why, nowadays, marriages seem to be built a good deal like automobiles,

rather for speed than for endurance!

Now, considering Mary’s tragic fate, you can readily

understand that William could never hope to be buried in one tomb with her,

but he did the best he could, under the circumstances. The fortieth verse of the song assures us that

he used to go out to that hill every day, and that is how it came it be called

William’s Hill, and there he used to sit

“And mourn by day and grieve by night

Until at last, his heart did break,

And he lay down and di-i-ed.

“Tiddy-fol-lol-dol-lol,

Skiddy-ki-di-do-bim.

Till he lay down, and di-i-ed.”

Just at your feet, curved about like a baby crescent

in the lap of the hills, you would see my little New England village, and just in the heart

of the village a little brick church. Do

you know, I like that expression, “the heart of the village”? A great city may have its parks, and its boulevards,

but it seems to me that it takes a little village to have a real heart, and

its [it’s] always seemed such an

appropriate thing to me too, that just in the heart of the village one should

find a little church.

Whether it is that people aren’t as queer as they used

to be or whether it is that I am losing some of my sense of humor as I grow

older, I’m sure I don’t know, but whenever I think of the kweer karacters

I have known first of all my mind turns back to that little New England village

of mine, to the little brick church just in the heart of the village, and

to some of the quaint and interesting people that I used to meet there from

week to week.

We used to take a great deal of pride in those days

in the fact that we used to have in our congregation, as a frequent guest,

the only man, so far as we knew, who had ever been able to get ahead of P.T.

Barnum, in a trade.

P.T. Barnum, you remember, was the one who first gave

rise to the saying that “The American people love to be humbugged.” And it was acting on this belief that led him

to start his circus, which in the beginning, was not all the gigantic affair

that it afterward became, but simply a collection of freaks and curios, which

he gathered from every quarter.

So it is said he was very much delighted one day, when

he received a letter from this small Vermont boy, saying he had in his

possession a cherry colored cat that he would be very glad to sell to Mr.

Barnum for a moderate price.

Mr. Barnum immediately saw the advantage it would be

to him to have a cherry colored cat to add to his collection, so he sent the

boy a railroad ticket to Springfield, Mass., the nearest place where the

circus was to appear, with a pass to the circus and all the sideshows.

The boy went down, and he had the very best kind of

a time, as a boy always can at a circus, you know. He ate peanuts, and popcorn, and drank pink

lemonade, until, as he used to say himself in telling about it, he was so

full he could still “chaw some but he couldn’t swaller any longer.”

Then at five o’clock, the appointed hour, he appeared

at Mr. Barnum’s tent with the cherry colored cat tied up in a sack.

Mr. Barnum’s face was wreathed in smiles as you see when he saw this

new freak almost within his grasp, but it is said his smile turned to a frown

of displeasure when the boy untied the sack, and out jumped a coal-black little

kitten. And Mr. Barnum said, “See here,

boy! I thought you told me you had

a cherry colored cat for sale!”

“Yes, sir, I did, sir, and this is a cherry colored

cat! This cat is the color of a black

cherry.”

And it is said that when Mr. Barnum saw that all the

American people, even himself, could be humbugged, his smile faded quite away

and he looked like this. [This may have been illustrated by Mrs. Fisk

turning her picture upside down.]

Those who used

to lead us in the Service of Song

Our church was an old-fashioned little building with

the singers’ seat high up in the rear, and the congregation used to rise and

turn about in their pews with their backs to the minister while they watched

the choir rend the anthem.

In those days, too, there was a motto painted on the

wall that said, “O Worship the Lord in the Beauty of Holiness.”

But the spirit of modernization has struck that little

brick church. The singers’ seats have

been moved around now, in back of the pulpit, and a new motto has been painted

on the wall, that says, “O Sing unto the Lord a New Song.”

And the last time I was home on a visit, the choir

sang it. At least, I think it was a

“new song.” I had never heard it before,

and I couldn’t understand a single word they said.

Now I’m not one of the kind of people that are always

mourning for “the good old days”, and thinking that “the times that are past

are the best,” and yet I must confess that that day I experienced a sense

of homesick longing for the days that are gone and the voices of our old-time

Village Choir.

Mis’ Babbitt sang soprano.

Her eyes were black as jet,

And the neighbors said her temper’d raise your hair,

But I used to think of Angels,

An’ I thought I heard ‘em sing,

When she used to sing soprano in our choir.

Nell Smith, she sung the alto,

I suppose she weighed a ton!

When the Lord made her, for flesh he wasn’t spare.

An’ she used to puff,

An’ haul for breath,

An’ act like she would burst,

When she used to sing the alto in our choir.

Elton Barker sung the tenor,

He was bald as any egg.

His head, it couldn’t boast a single hair;

An’ he used to sing in nasal tones,

About the “doleful tomb”, and the “grave”,

That yawned wide open for our choir.

Hark! from the tombs, a doleful sound,

My soul attend the cry,

“as I am now, so you must be.

My soul, prepare to die.”

I had been telling some of these stories in the West,

a number of years ago, and at the close of my entertainment, a lady came up

to me and said, “Oh, Mrs. Fisk, you don’t know how much we do enjoy hearing

about those funny New England people of yours, but do you know, I’m a little

bit curious to know – what in the world do you talk about when you’re back

East with them?”

“Well, then,” I said, “I tell about you western folks.”

“Oh, but we western people aren’t so funny. We don’t do such queer things.”

All the world is queer but thee, and me, you know.

I suppose it was along about this same line of thought

that I had a rather amusing little experience a number of years ago with a

gentleman out in Iowa. He had been very kind to me, he had helped me

set up my easels, and take them down again, and had given me safe escort to

the hotel, a courtesy that I very much appreciated.

On the way home he said, “My I sure do wish you could

stay in our town a spell longer. We’ve

got some awful queer characters in our town an’ I’d like to introduce you

to some of ‘em. You’d like to put ‘em

in your entertainment. But now you’ve

got to go away on the mornin’ train, you won’t get to meet any of ‘em.”

I wasn’t so sure of it, though, for when I bade him

goodnight I attempted to thank him for the kindness he had shown me, but with

an air that was truly Chesterfieldian he waved it all aside, as he said, “Oh,

that ain’t nothin’. I like to help. I like to help anybody. Now you know there are some folks that are awful

willin’ to help a young, pretty lookin’ girl, but it don’t make no difference

to me how old and homely a woman is, I’ll help her just the same.”

It is true, however, that some of the most interesting

people I have met have been those in the West, particularly of that part of

the West known as the cattle country. A

number of years ago I found myself storm-stayed in a little hotel up in the

cattle country. Two of the cowboys

were marooned there, too, and we all sought the only warm place there was

in the building, the little office. For

a while a dead silence fell upon the room, for it there is anything in all

this wide, wide world of which, I suppose, those great rough and ready men

are afraid, it is of a single American woman. But at last, convinced that I was safely engaged

in my writing, they began to talk and swap yarns with each other.

“Well,” said one, “I reckon I been as lucky as most.

I’ve rode everything this side of the Platte, an’ I ain’t never had a bone

broke yet. But now, there’s Bill –

Bill’s diffrunt. Why I don’t believe

Bill’s got a bone in his body haint been broke up, one time or another.

“I remember of a good many years ago, I’se out huntin’

coyotes with Bill, an’ all at once his horse stepped in a gopher hole, an

throwed him. Now you know, that’s a

funny thing. You take anybody that

ain’t used to ridin’, an’ you let his horse throw him, he gets so scared he

gets limber all over. Well, when he

comes down limp, that a way, it don’t seem to hurt him much. But you take a man that’s used to ridin’, and

he feels his horse a-goin out from under him, it makes him so plumb mad, that

he stiffens up all over. Well, when

a man comes down stiff that a way, somethin’ got to bust! Well, that’s the way it was with Bill that day

I reckon, but he got right up an’ went along agin, an’ I didn’t think he was

hurt much. Well, along came night,

I left Bill at his shack an’ I rode on toward the ranch alone, but just as

I’se goin’ over a little raise, I turned to wave goodbye to Bill an’ I see

Bill pitch off his horse, and then I knowed Bill was hurt. I rode right back to him an’ I says, ‘Bill,

be you hurt.?’

“‘I dunno," says he, "I didn’t think I was

but I guess I be."

“Well, I opened up his shirt, an’ I seen his collarbone,

just sunk right in there. ‘Twas snapped

off short in the middle. Well, I put

my thumbs behind his shoulder-blades, an’ I pressed up slow an’ easy, an’

I seen them bones just riz right up into place again. So then, I knowed what I must do. I took Bill into his shack, an’ I set him down

in a chair, an’ I pressed them bones up into place, an’ I then I tied him,

just like I had him, an’ I kept him tied up that way for two weeks, an’ you

know, them bones knet, as purty as any bones you ever see.”

“Well,” said his companion, “’Twas kind of rough on

Bill, wasn’t it? Why didn’t ye strop

a board to his back when ye got his bones into place, an’ then he could a

kinder moved around, and enjoyed hisself.”

“Huh! I don’

know. I never thought of it. The only thing I was thinkin’ was that I’d got

to get them bones tied up into place, before they had a chance to slep, and

knet wrong. An’ anyway, that’s the

way I done it. I tied him up in that

chair there an’ I kep’ him tied up for two weeks, an’ I fed an’ watered him

just like you would a horse. But a

point I want to make is this: There

ain’t no use in doctors! Now if we’d

been down near a settlement they’d uv had a doctor in there, an’ he’d a sweat

an’ fussed around an awful; lot, and he couldn’t have set them bones no better’n

I done it. I reckon we’d of had a time with Bill as we

did with Baldy Bradley, when he had the mountain fever. They had a doctor in for Baldy, an’ he give

him medicine. It looked like harness

oil, an’ it smelt like a burnt boot, an’ it tasted like the both of ‘em stirred

up together, an’ you know, eberytime it come time to hand old Baldy a jolt

of the stuff, it took three of us able bodied men to turn the trick. One of us had to set on him, an’ one had to

open his mouth, an’ the third had to guide the spoon. No sir, no doctor could of set them bones no

better’n I done it, an’ I tell you, when you get off there a hundred an’ twenty-five

miles from everybody an’ everything, you’ve got to learn to do things for

yourself.”

And there is the cowboy’s outlook on life. He is truly Nature’s independent nobleman, and

he can do everything for himself, from cooking his own grub to breaking a

bucking bronco, or closing a companion’s eyes in his last long sleep.

At last one of them said, “Well, come on, let’s go

out an’ have a drink.”

“Nope,” said the other, “I don’t drink.”

“You don’t drink! Why

I drink.”

“No, I don’t drink.

I ain’t drunk a drop for fifteen years.

Fifteen years last August, ‘twas, that I swore off, and ‘twas all because

a train was late one night too. I’d

drawed my month’s wages an’ I went down to Hackett, an’ I had a high old time,

I tell you. I got so drunk that I didn’t

know whether I’se afoot or horseback. Well, when it got along about train time I went

down to the depot. The agent said the

train was late, he didn’t know how much, but ‘twas some late. Well, I didn’t want to go back up to town, –

‘twouldn’t a done me any good anyhow for I was broke so I thought I’d just

sit down in the depot, an’ wait for the train.

But I soon saw that wa’n’t going’ to do, for I’se so drunk, I’se going’

sound asleep, an’ I was afraid the train’d come and go off without me, an

I couldn’t afford to get left down there, for I didn’t have a cent left. So then I thought I’d walk up and down the platform

a spell, but I soon see that wouldn’t do either, I’se so drunk I couldn’t

walk. So then I propped myself up into

a kind of an angle, where two sides of the depot come together, an’ you know,

I stood there all night, before that train finally come along. But you know, I had time to do an awful lot

of thinkin’ while I was standin’ there, an’ thinks to myself, ‘You big fool,

you! To work hard a whole month, a

punchin’ cows, an’ then go an’ blow the whole thing in, in one big drunk! An git so

drunk, too, that you can’t stand up, an’ you can’t set down, an’ ye can’t

walk, but you got to stay propped up like a corpse against the side of this

depot all night.’ An’ says I to myself,

I won’t never drink another drop of liquor, as long as I live. An’ I ain’t.

I ain’t drunk a drop from that day to this.”

“Well, I drink,” said the other, “But I tell ye there’s

one thing I won’t never do. I won’t

never go back a second time to get a drink to a place they’ve kicked me out

of once. You know, that’s something

I can’t understand, can you, why it is a man’ll go back to a place he’s been

kicked out of?”

Then it was that I heard one of the best bits of philosophy

among the temperance line that I have ever heard, for the other answered,

“Yes, I can understand that all right. I can understand why a man’ll go back a second

time to a place he’s been kicked out of. Why,

if you kick any hog in the head, he’ll go right back to his slops again.”

[Ed. note: Here she introduces

a piece she probably sketched out in 1912 and in shorter length, that she

entitled “Among the Sandhills – The Cowboy’s

Prayer.]

But, strange as it may seem, the one cowboy whom I

really feel I know best, in all that wild, free land, is a man whom I have

never seen. A few years ago I once

again found myself marooned in a little town in the cattle country, in the

hills of Wyoming. It seemed to have been an off day with the cowboys,

and all day long they had been sifting into town, until by night the town

was full of them. I could hear their

loud voices long before I came into the hotel from my evening entertainment.

The air was thick and blue with smoke, but every pipe and cigar was

held aloft, and a dead silence fell upon the little office till I had passed

out of sight around a bend in the stairway.

Then the talk and laughter broke forth again.

It veritably seemed as if that must be a House of Cards,

for as I made ready for bed, I could hear every voice in the little building.

Just below me in the parlor, were the landlord’s daughter and her sweetheart,

engaged in that sweetest of all human occupations.

Somewhere I could here the monotonous rattle and whir of a sewing machine,

evidently the landlord’s wife, engaged in some belated Saturday night sewing. Just through the partition in the next room,

I could hear the heavy stertorous breathing of a man who had gone to bed early...evidently

too weary to join in the fun and hilarity downstairs, and was seeking by sleep

to “knit up the raveled sleeve of care.” And always below in the office was the murmur

of the cowboys’ voices, and occasional loud bursts of laughter.

But there seemed to be one voice that led and dominated

them all – a great, rough voice – one of the kind that instinctively makes

a woman shudder. At last I heard him

boom out a goodnight to his companions, and come up the stairway. Every step creaked beneath his heavy tread. He came down the hall, and turned into the room

just across from mine. Then fear, which

is seldom a guest in my heart, took me by the throat with both hands.

In a perfect panic I stole from my bed, and made sure that my door,

and both my windows were fastened tight.

As he made ready for bed, I could hear him humming

a little tune, if a man with such an enormous voice can ever be said to hum,

and then the music changed into words and because it was a House of Cards,

I couldn’t help but hear every word he said, and this was it:

“For all the mercies, an’ blessin’s of the day, we

thank Thee, Lord. An’ now its come

night an’ time to go to bed, we ask You to be with us, an’ watch over us still. Bless all my folks tonight, where-ever they

be. Bless Uncle John, an’ his folks,

an’ bless Aunt Matt, an’ her folks, – an’ Lord, bless me. You know what an awful hard time I have gettin’

along, an’ won’t You just help me tomorrer, an’ help me be strong, an’ help

me to be sweet, an’ help me to be clean of heart! For Jesus’ sake. Amen.”

And that night I slept the night of perfect peace,

because in that one moment it had been given to me to see that underneath

that great rough exterior there dwelt the simple faith of a little child,

who asked for help “just for tomorrow.” And

often when the evening shadows draw long and purple, over hill and valley,

my mind turns back to that rough cowboy in his lonely little shack among the

Wyoming hills, and I join my prayer with his, that God indeed may help him

to be that finest of all American gentlemen, – strong, sweet, and clean of

heart.”

[Spacing in the typescript may indicate there

is a break in the program here, or that portions of this are modular and can

be rearranged, added or deleted.]

I

always feel a good deal of hesitation about drawing pictures before an audience

like this, because I realize that my pictures are going to appeal so differently

to ones of you.

A prominent lecturer a number of years ago – I think

it was Talmadge – asked this pertinent question: “Is life worth living?” A wag gave the impertinent answer: “It depends

on the liver.” So I realize that a

good deal depends on your livers, as to how my pictures shall appeal to you.

Now if I draw a large yellow globe, like this upon

the easel, and could go through this audience, and ask you, one by one, what

you think it represents, I should receive a surprising variety of answers. These small boys, down in front, would answer

without a bit of hesitation, “Why, it’s an orange.” Because boys, you know, are always thinking

in terms of things to eat. But ask

the small girls who are here, what they think it represents and they would

answer just as quickly – perhaps because girls are fanciful and poetic – “Why,

it’s the Man in the Moon.”

But take that selfsame couple after ten or a dozen years

have passed over their heads, and ask them what they see in the great yellow

globe, and their answers would vary yet again. They would answer quite as quickly, but this

time in perfect unison: “O-o-o-oh! It’s

a honeymoon.”

Oh, the honeymoon!

The most saccharine and useless period of all a person’s existence! I was entertained not so very many years ago,

in a home where there was a honeymoon of the most virulent nature. They were a lovely young couple – indeed I think

I might say they were about the most thoughtful people I ever saw, for they

thought I must be very tired after my entertainment and wouldn’t I like to

go immediately to bed.

But hardly were the curtains drawn between my room

and the living room, than I thought I heard them having refreshments out there,

all by themselves. I thought they were

opening pop bottles – but they weren’t.

Well, it was all right. It sounded good to me. I approve of honey-moon kisses. The only trouble is, too many folks consider

them as just fishing smacks, and they are left safely tied up ashore when

the one great voyage is begun. And

that is why, I fancy, there are so many wrecks along the sea of life, and

if there are any of you men here tonight who have grown careless of the tender

attention of your honeymoon days, I would beg that you go home tonight, and

try to renew that old sweet time.

You may find it a little hard at first, from lack of

practice, – indeed you may have shared a time as one old gentleman who did

try to follow such advice, but his wife drew away in horror, from his very

first caress, as she said, “Why, you get away from me, you old fool! What’s the matter with you anyway? Are you drunk again?”

Perhaps it is because of this very carelessness, then,

that if we should ask this self-same couple after another ten or a dozen years

have gone over their heads, what they see in this great yellow globe, their

answers would vary yet again. Nine

times out of ten, the wife would answer without even a second glance, “Oh,

I suppose it’s a dish pan!” But ask

her husband what he thinks it represents and he would answer, “Why, it’s a

pie.” because, you see, his mind has gone back to its boyhood’s estate, and

he’s once again thinking in terms of things to eat.

A truth that was well recognized by the old lady who was approached

by a young friend, and asked how she might always be sure to keep her husband’s

love through life. And the old lady

sized up all the wisdom of the ages in just three words, “Feed the brute.”

So, if you should ask him what he thinks it represents,

he’d say, “Why, it’s a pie.” And if

you should press the question a little farther, and ask him “What pie?” a

bright smile would come over his face, and he would say, “Why, it’s the pie

that mother used to make!”

O, those pies that mother used to make! How much we women have heard of them, haven’t

we?

But, do you know, there is one thing that has always

struck me as a little bit queer, and that is, how little the men ever have

to say about the pants their mothers used to make.

They praise her doughnut, and her pies,

Her coffee and her steak,

But where’s the man that sighs for pants

Like mother used to make!

She used to take a pair of pa’s

When they were old and frayed,

And decorate ‘em with a patch

Of some contrasting shade,

And take them in around the waist,

And cut the knees off, too,

And say that they for every day,

Were just the thing for you!

And then she sent you off to school,

And when you wouldn’t go,

She wondered what got into boys

That they played truant so!

Yes, still you praise her pie, her cake,

Her coffee and her steak,

But where’s the man that sighs for pants

Like mother used to make!

I could never understand this myself, till a little

while ago. I was visiting a friend of mine who was just starting her little

boy off to school in his first pair of home-made trousers. At first, the child was just delighted with

them, and he said, “My, ain’t it funny about these pants? They’re tighter

than my skin.”

And his mother said, “Why, no, dear, they aren’t either

tighter than your skin.”

“Well, they are, too, because I can sit

down in my skin just as easy as anything, but I can’t sit down in these pants

at all.”

But his joy was soon turned to sorrow for on the very

first day that she started him off to school, it didn’t seem as if he had

barely more time than to get to the schoolhouse and back, than she heard him

coming down the road, crying as if his little heart would break. And his mother ran out and said, “Why, Freddie,

dear, what is the mater?”

“Ba-a-a-w! The

boys all made fun of my trousers.”

“The boys make fun of the nice little panties made

for her boy! Why, what do they say?”

“Ya-a-aw! They

say – they can’t tell, by my looks, whether I’m comin’ or goin’.”

I never

think of poorly clad or poorly understood children, that it doesn’t carry

me back to the place where I first attended school.

A little red school house it was, at the top of a long

hill, down which we children had the most magnificent coasting in the winter

time.

Just at the foot of the hill stood Dascomb’s Store,

a long white building, with a pink door, on which the somewhat eccentric storekeeper

had painted this motto: “Be just, and fear not.”

I well remember one day when I was coasting down the

hill, I lost control of my sled. Before

I could regain it again I had gone the full length of that hill, had crashed

through that pink door, and had gone half way across the store building. It wasn’t necessary for me to go any farther

than that, for the storekeeper came the other half of the way to meet me. We had a little conversation, – at least, he did, and I didn’t think he was very

just, and I found it absolutely impossible to “fear not”, as I gazed into

his blazing eyes.

It was in this little red schoolhouse that I learned

my first lessons, my a – b, abs, and my first arithmetic lesson, which I remember

very well to this day, went this way, “Two arples” – and I don’t know where

my teacher did come from, Bawston, I suppose, but anyway, we had to say arples

– “Two arples and two arples make four arples, and two pears and two pears

make four pears, but you cannot add arples to pears, nor pears to arples.”

I used to say it over and over just like that, because my mother taught

me that I must always be a good girl and do just what the teacher said; also

I had tried a few little experiments of my own, and had found out I would

better do what she said, too. So I used to say it over obediently, “Two arples

and two arples make four arples, and two pears and two pears make four pears,

but you cannot add arples to pears nor pears to arples.” But I couldn’t understand it at all, for I added

apples to pears and pears to apples every day out of my lunch basket, and

it never hurt me any.

How different that is from the table of values which

the American children are learning nowadays, which goes for substance, if

not the exact phraseology” “Ten mills

make one trust; ten trusts make one combine; ten combines make one merger;

ten merger make one magnate, and one magnate makes the money.”

And yet we cannot too severely criticize Big Business,

when we stop to realize that it has been ordained from the very beginning

of time. Why, did you ever stop to

realize that even Eve was made for Adam’s Express Company?

But the crowning glory of the little red schoolhouse

was in none of these things, but rather in a great old butternut tree that

grew across the road, and the crowning glory of the butternut tree was a great

broad limb that stretched out its hospitable length toward the schoolhouse. And on this limb the children had woven a most

wonderful game, which they called the “swing and drop.” It consisted of climbing out on the limb as

fare as one dared, swinging down by the hands, and dropping to the ground

beneath. Anyone who had accomplished

this was then given a seat on the broad limb where they might sit, and swing

their feet and sing songs.

Now I had never been able to accomplish this, for my

mother had always taught me that I must be very “careful of her only daughter,”

but at last the iron entered my soul. I

realized that I would just as soon be dead, as not to have a seat on that

broad limb, so one day I surreptitiously set my mother’s clock ahead a half

hour, and in that way I got an early start to school.

I hung up my hat and dinner bucket in the entry and went and stood

looking up at the great tree. I am

sure I know how all great sols feel when they start out on the world’s adventures.

Why, that morning I could have sailed the Seven Seas, or discovered

the North Pole.

At last, realizing that time was flying, I climbed

out on the broad limb, as I had seen others do, swung down by my hands, shut

my eyes, breathed an involuntary prayer for safety, and dropped to the ground

below. When I opened my eyes again

it seemed strange to me to see the little clouds still floating lazily by

in the blue above, and the birds still singing their undisturbed songs, for

it had seemed to me as if all Nature ought to stand still in wonder and amazement,

that I, Marion Ballou, had at last done “the swing and drop.”

To make my accomplishment secure I did it again and

yet once again. Then when the other

children came to school, I said, “Hm! I

can do the “swing and drop.” And with

one accord they all took up the chant, “Huh! cowardly calf, you can’t either.

You don’t dast.”

“Aw, I do, too, dast,” I replied and then and there

I proceeded to do the swing and drop before their unbelieving eyes. After that I was accorded a seat on the broad

limb, where I might sit and swing my feet, and sing songs with the rest, and

I can truly say that none of the accomplishments of my later life have given

me one half the pride that it did that morning when I first learned to do the “swing and drop.”

But whenever I think of that little red schoolhouse

I always think of some of the boys and girls who went to school with me there

in the early days.

One of the first who always comes to my mind is John

Keating. He was a roguish Irish lad,

with black hair, and blue eyes, and a long, wicked tongue, which he used to

wear, most of the time, sticking out like this, at me.

Oh, that boy! He

had the most unholy way of getting us all into mischief, and then shinning

out of it, and leave us to get out the best way we could. Its seems strange to ,me, when I think of this

propensity of his, that none of us ever realized what his profession in life

was to be, but we didn’t, and there was a prophesy that was rife in that little

town, that “John Keating was certainly born to be hung!”

So I was greatly surprised when I was home a few years

ago, when my father came home from a State’s Court Case, of considerable importance,

and said, “Why, do you know, I saw one of your old schoolmates at court today.”

“Is that so,” I asked, “Who was it?”

“Why,” he said, “It was John Keating.”

“Well, I said, “I am not at all surprised at that.

What did they decide to do with him anyway?

Hang him?”

“Hang him!” he exclaimed. Why, he’s the State’s Attorney! He’s as smart as a whip.”

Another boy who was a close second to him in all the

mischief that was afoot was Charlie Howard.

I don’t know whether the teacher would rather have him present with

all the mischief he stirred up, or whether she would rather have him absent

with the comparative quiet, but I will say this for her, she was a faithful

soul, and she pretty nearly always sent for him.

She always knew just exactly where to send, too, for on his way to

school he had to pass a big mill, and like Budge and Toddy, he loved to see

the wheels go ‘round.

But I used to think sometimes that her sole and only

object in getting him there was that she might keep him out on the dunce stool,

and Charlie Howard was very far from being a dunce, if he could ever once

he got interested in anything.

My last distinct memory of him is one day when, in

our arithmetic class, we were studying that bane of all childhood, – fractions! On that particular day we had a lot of imaginary

logs of wood to saw up into given lengths, and always there was a troublesome

little fraction left over. When at

last the class was called to order Charlie Howard came out, with his freckled

face just all abeam. To be sure he

had only solved one of his problems, for he had spent all the rest of his

time, figuring out a brilliant scheme by which he might use up all those little

fractions of wood, making spools, or chair trimmings, or something of the

kind, – I don’t exactly remember what it was, but anyway, we could al make

an independent fortune by it. I am

sure it was a good scheme, too, but the teacher couldn’t seem to see it that

way, and after the rest of us were dismissed, Charlie Howard was kept in to

finish his problems, and my distinct memory of him, is of seeing his freckled

face pressed against the window pane, a little bit wistful, but after all

bearing the smile of accomplishment.

You’ll be surprised to know that he only waited to

finish the eighth grade, and then disappeared from school. One of the last times I was home, I was interested

to inquire what had become of him, too, and they told me he had gone down

into Massachusetts, and fortunately had fallen into the hands of a man who

understood boys and their peculiar activities, who had got him interested

in a trade school; and later in business and today Charlie Howard is one of

the biggest, and one of the richest, business men in the whole state of Massachusetts,

so I saw that the wheels had turned to some account in his head, after all,

and I have always felt that the great success he has made in life has been

because he was always studying out some scheme by which he might save the

little waste pieces.

Now of the one little girl who went to school there,

in whom I trust you are mainly interested, there really isn’t much to say. I was kind of a non-descript little individual,

with long, mouse-colored hair, which my mother used to braid and tie with

pink ribbons, every morning when she started me off to school. I guess those boys thought my braids were bell-ropes,

– they used to pull them most of the time, and I have always thought that

accounted for the extreme length of my hair, – it was nearly torn out by its

roots in its early age. Between those

two boys I certainly had a hard time, and to make this picture a perfectly

life-like one, I have drawn myself here, between the two boys, and people

who see this picture here and see me now remark on how much I’ve kept my baby

looks.

There was another boy who went to school with us there,

in the early days. His name was Willie

Smith. Did you ever notice how many

perfectly lovely people there are in the world by the name of Smith.

I could never understand until a little while ago where so many Smiths

came from. Then one day, as I was going into San Jose, our train was pulled in on

a sidetrack, opposite a great red brick factory. Heavy laden dray teams were driving in and out;

through the windows I could the whir and flash of belts and machinery, and

men and women hastening back and forth at their toil. Altogether it was such a scene of unusual activity

that my curiosity was aroused as to what sort of place it might be, so I lifted

my car window and looked out, and there I saw painted in great white letters

on the side of the red brick factory: Smith Manufacturing Company.

Now I have never learned whether Willie Smith’s parents

were manufactured there or not, but Willie came to our school, and he was

a lovely boy. He had blue eyes and

red lips, and yellow hair, and a clean neck!

He was the only boy in our school that had a clean neck, and his mother

used to start him off every morning with a great white tie beneath his chin. Oh, we girls thought he was just sweet, but

the boys said he was a sissy.

Near our schoolhouse was a great bed of wild strawberries,

and always at noons and recesses, in strawberry

season, you could find us children there gathering that luscious fruit, Till

“Our lips were kissed redder still

By the strawberries on the hill!

But it wasn’t very long before we noticed that Willie

was never one of our number, so we said one day, “Why, Willie, don’t you like

strawberries?”

“Yes,” he answered, “I like ‘em all right, but I don’t

like to pick ‘em. I don’t like to get

my fingers dirty.”

“Oh, well then, Willie,” we said, “we’ll pick ‘em for

you. We’ll pick six berries for one

kiss.” Poor Willie! He nearly died from overeating.

Well, at last came the time when he, too, went away

to seek his fortune, like all the rest of us, was gone for about two years,

and then came home, a poor miserable wreck.

For two more years he lingered on, a burden to himself, and to everybody

else, and then he died, a victim of his own dissipations. Whether it was that he was always afraid of

getting his fingers dirty by honest toil, or whether he was always waiting

for somebody to pick his berries for kisses, I’m sure I don’t know, but of

all the boys and girls who went out from that little red schoolhouse, he was

the only one who made a colossal failure of life.

I haven’t any moral to teach in the little tale, and

I wouldn’t for one moment want to be understood to say that all good boys

are going to turn out bad or that all bad boys are going to turn out good. What I would rather say is this: that primarily

speaking there are no such things as bad boys. There are quiet boys, – a few, – and active,

mischievous boys, but if I had to take my choice between them, I should every

time choose an active, mischievous boy, whose blood is full of good, red corpuscles,

and then I should pray for wisdom, to guide his activities aright, for it

is upon this one question, whether his activities are guided right or wrong,

that depends the whole future course of his life, and whether it shall eventually

spell success or failure.

It

is just along this line of thought, of directed or misdirected energy, that

I want to introduce you to two other old friends of mine, men who were born

at about the same time, under much the same circumstances, and were blessed

by Nature with much the same gifts, yet who have left behind them a very different

heritage to the world.

One of these was known far and wide throughout our

countryside as Uncle Ben Hathaway, and he was a wonderful fiddler. There was never a country dance, or a barn-raising,

or a merry-making of any kind, that was counted complete unless Uncle Ben

was there with his fiddle, and it almost seems, as I speak of him tonight,

that I can once again hear his voice, as he used to call out the figures in

the dance: “Balance your partners, and all hands around.”

The story of how he had become such a famous fiddler

was a familiar one to all of us, for in his boyhood it was the custom for

every child to have his “stent” of work to do before he could play. So one day, when his father went away from home

he left the boy a number of rows of beans to hoe, but hardly was the old man

out of sight, when the boy broke forth into bitter lamentations, and he said,

“I don’t want to hoe beans! I’d rather

die than hoe beans!”

And his mother said, “Why, Bennie! What do you want to do?”

“Oh,” he said, “I want to fiddle. I’d a heap sight rather fiddle than hoe beans.”

“Well, then, Bennie,” his mother said, “if that is

the way you feel about it, you go an’ fiddle, and I’ll fix it up someway with

your father about the beans.”

And that was the way Bennie grew up, – always fiddling,

and always waiting for someone else to hoe his row. So he grew to young manhood’s estate. Then came that tragic day when a dark cloud

arose over the southern horizon of our country, the dark cloud of war, and

because Uncle Sam’s need of men was great and his eyes were keen and sharp

to detect those who were strong of arm and limb to serve him, and seeing that

Uncle Ben was such a one, he touched him upon the arm and said, “Come,. follow

me.” Now this was not at all to Uncle

Ben’s liking. I suppose he felt he

would rather die than go to war, but Uncle Sam’s mandates might not lightly

be disregarded, and he was cast into a sad state of mind indeed, until one

day, wandering around the farm barefooted, as was his wont, and coming into

the woodshed so, he was seized with a brilliant idea, which seemed to him

little short of inspiration. Lifting

his great bare foot, he set it upon the chopping block, seized the axe, and

with one blow severed his great toe. This

rendered him exempt from service on the ground of physical disability. Among those who were too short sighted to see

the real cowardliness of the act, it passed almost as a kind of bravery, but

this, in brief, is the story of how it happened that Uncle Ben limped, and

fiddled, all though his life.

But there came a time when another messenger touched

him upon the shoulder and said, “Come, follow me.” This time not a messenger that might be put

off by any subterfuge, or any excuse, – the messenger whom we call Death. So Uncle Ben laid down his fiddle and his bow

and went away on the long journey from which there is no returning. Because he had been a popular man, the people

came in great crowds to his funeral, and the women and children went inside

the house, with the mourners, but the men stayed outside and talked together,

and they said, “Well, Uncle Ben’s gone! He

was a might fine fiddler! I wonder

who we’ll get to do our fiddlin’ for us now.

I suppose we’ll have to get Juddy Jennison. He ain’t near as good a fiddler as Uncle Ben

was, but I guess he’ll have to do. Yes,

we’ll have to get Juddy Jennison.”

So it was that Juddy Jennison took up the fiddle and

the bow, where Uncle Ben’s marvelous hands had dropped them, and though he

could not play as well as Uncle Ben had done, yet in a little while the young

people found they could trip the light fantastic to his music quite as wall,

and soon Uncle Ben and his wonderful playing became only a memory and a tradition

throughout our countryside.

About the same time there was born, across the state

line in New Hampshire another lad.

He, too, was gifted musically, and I do not doubt, but that time him

too often came the thought that he “would rather die than hoe beans,” but

his father and mother were of wiser sort, and they taught him that it was

“work first and play afterwards.”

But music will out, so one day when the work was done

he took the hollow stock of a seed onion, and from it he fashioned himself

a flute, and so cunningly had he devised it, that he could really play upon

it. When his father saw what the boy

had done he felt that perhaps such genius should be encouraged, so he bought

him a seraphine, or ancient instrument familiar to few of you here tonight. On this the boy and his sister learned to play.

They played everything they knew, and when these were exhausted they

made up songs of their own.

So the years passed on until the young man was twenty-one

years of age, then he went down to Boston, purchased a horse and wagon, and

a little melodion and started out through the countryside giving concerts

in schools and churches, and wherever they would give him a hearing.

Then came the time when Uncle Sam touched him upon

the shoulder and said, “Come, follow me.”

I do not doubt but to him, as to every strong young man, came the horror

ands the dread of war, but it never occurred to him to seek an excuse why

he should not enter his country’s service.

He was away, the night the summons came, and all the way home a little

song, both words and music, kept persistently running through his mind. He tried to put it from him, but in vain, so

when he had reached home he took down an old violin from the wall, an instrument

he had never used before and never did again in the composition of a song,

and wrote the simple little piece.

A few days later he went down to Concord, New Hampshire,

to take his examination for service, was found to be physically unfit, and

was dismissed, so he never did bear arms for his country, but who shall say

that he did not render her just as effectual service, for about that time,

there was a demand for a song, by which the soldiers might march, and sing

in camp. The Oliver Ditson Company

had advertised for such a song, and half trembling at his own temerity, the

young man sent down the simple little song he had written the night of his

draft, offering to sell it to them for the modest price of fifteen dollars.

They tried it over, were disgusted with it, because

of its simplicity, and refused to have it at any price. They hired a musician of considerable note to

write such a song for them, purchased and published it, but it fell still-born

from the press. The soldiers simply

wouldn’t sing it, that was all. Then,

because the call was insistent, and the need was great, they bethought themselves

of the little song which they had once refused, purchased and published it,

and in less than six weeks it was being sung by every Southern campfire, and

in every Northern home.

I

very well remember one day when I was a little girl, seeing an eccentric looking

man, come driving into our yard. He was driving a brown horse, hitched to a pink

express wagon, and in the back was strapped a little melodion. My father and mother received him with the greatest

joy, and the little melodion was set up in the kitchen, for he would have

nothing whatever to do with the parlor. I

have always liked to remember that that night I was allowed to sit up, far

beyond my usual bedtime, while I listened to my father and mother, and their

friend talk, often to be sure about things which I could not understand, but

I liked to listen to his kindly voice, and watch his gentle, genial smile.

I

very well remember one day when I was a little girl, seeing an eccentric looking

man, come driving into our yard. He was driving a brown horse, hitched to a pink

express wagon, and in the back was strapped a little melodion. My father and mother received him with the greatest

joy, and the little melodion was set up in the kitchen, for he would have

nothing whatever to do with the parlor. I

have always liked to remember that that night I was allowed to sit up, far

beyond my usual bedtime, while I listened to my father and mother, and their

friend talk, often to be sure about things which I could not understand, but

I liked to listen to his kindly voice, and watch his gentle, genial smile.

And at last they sang songs, sometimes songs in which

my father and mother joined him, sometimes songs which he sang alone, and

at last he told us this little story of his boyhood and youth, practically

as I have told it to you tonight, and sang us the little song he had written

the night of his draft, the song that has made the name of Walter Kittredge

known, and loved, all over our country.

“We are tenting tonight on the old camp ground,

Give us a song to cheer,

Our weary hearts, a song of home,

And the friends we love so dear.

Many are the hearts that are weary tonight,

Wishing for the war to cease,

Many are the hearts, looking for the right,

To see the dawn of Peace.

Tenting tonight, tenting tonight,

Tenting on the old camp ground.

We’ve been fighting today on the old camp ground.

Many are lying near,

Some are dead, – and some are dying,

Many are in tears.

Many are the hearts that are weary tonight,

Wishing for the war to cease,

Many are the hearts, looking for the right,

To see the dawn of Peace.

Dying tonight, dying tonight,

Dying on the old camp ground.

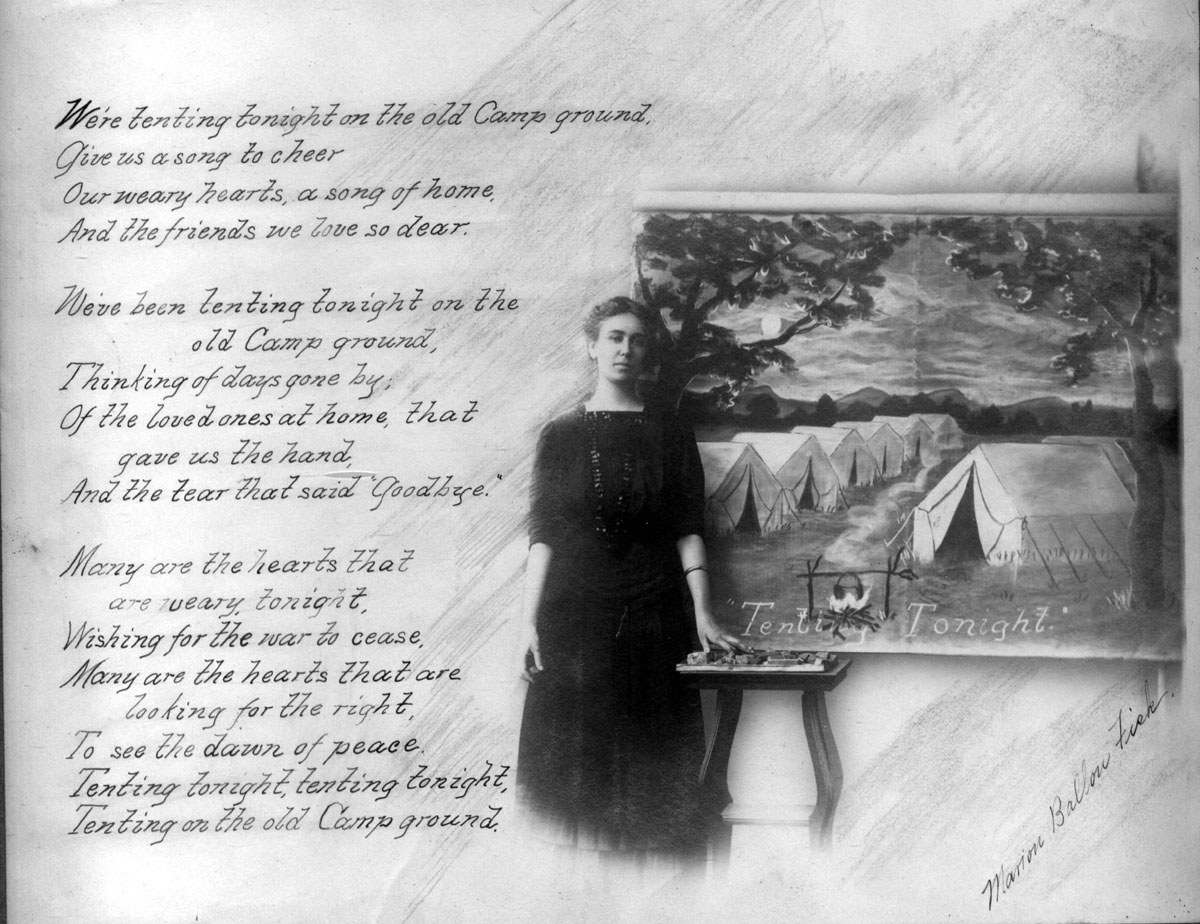

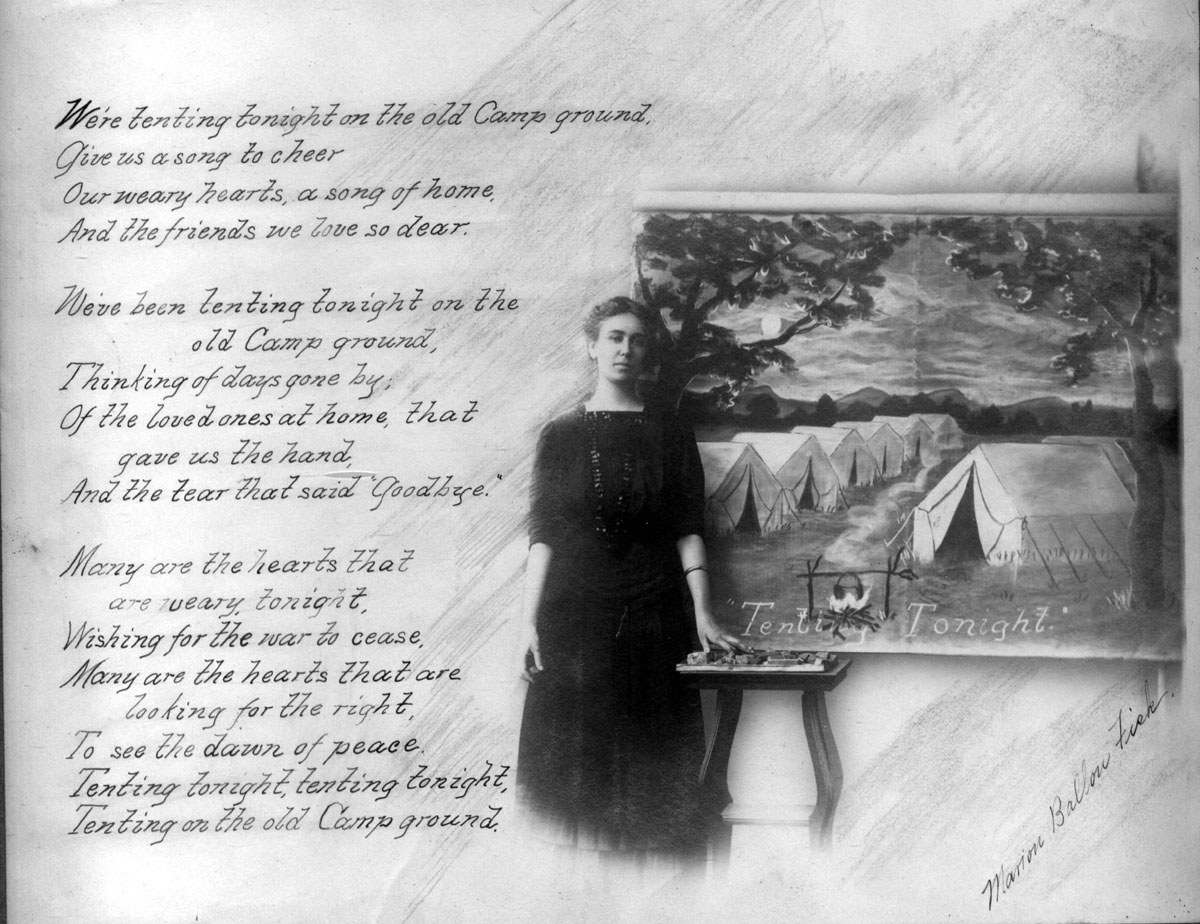

A photograph of Mrs. Fisk [reproduced

just above] shows her standing in front of her easel with her drawing of the

camp ground, and she has penned this alternative – additional? – verse:

We’ve been tenting tonight

on the old Camp ground,

Thinking of days gone by;

Of the loved ones at home that

gave us the hand

And the tear that said “Goodbye”

[Ed note: this photograph is not part of the collection but remains

with the Giersbach family.]

If

we could read one another’s hearts as we can read our own, I am sure that

we should find that most of the queer things people do springs from common

desire in the human heart, and that is the desire for happiness. This is as wise and right a desire as it is

universal, and yet in this, as in everything else in life, there are both

right and wrong ways of seeking for it. One

of the cleverest little stories along this line comes to us from the Emerald

Isle, “The Ashes of Old Wishes.”

It was a wonder night in the fall o’ the year,

when Dame Nature has grown most kindly toward her children, and allows them

all, every tree and bush and little shrub, to deck themselves out in their

garments of brightest hue, for one last frolic before she tucks them away,

safe wrapped in white, for their winter sleeping. A wonder night in Ireland, too, as all the good

people there know, for it was the night when the fairy folk walk abroad and

do kindly deeds to the children of men.

Darby O’Gill sat alone by his fire, with none to bear

him company, save Michael, the great cat.

Bridget and the children had gone to bed early that they might be ready

for early morning mass, but Darby sat by his fire and waited for of late years

he had made great friends with the fairy folk.

They often came to see him, and sometimes brought him a present and

this year, for some reason, Darby hoped his present would be an unusually

fine one. While he sat and wondered

what perchance it might be, he was startled by a little chuckle across the

fireplace. Looking up he saw that the

King of Fairies himself had come in and taken his seat opposite him.

Darby O’Gill greeted him cordially and the king said,

“Ah, Darby O’Gill, it’s a foine present that I’m after bringin’ you this avenin’!”

“Ah!” said Darby, “it’s glad indade that I am to hear

it! And what, might I ask, might it

be?”

“Oh,” said the king, “I’ve brought yez the foinest

jar of poteen that there is, in all ould Ireland ground.”

Then it was that Darby O’Gill’s heart took a cropper

and he fairly snorted in his wrath. “A

jar of poteen! A jar of poteen, did

yez say? And I thought the laist ye

wad be bringin’ me wad be riches.”

“Oh, now, Darby O’Gill!” said the king. “How often must I be afther tellin’ ye that

I’ll never ruin and spile ye by bringin’ ye riches!”

“Ah! Roon and

spile indade! As if anybody was ever

rooned or spiled by riches!”

And thereafter Darby O’Gill sat so glum, and so dour,

that he wouldn’t speak a word to the king, and so silence fell upon them for

a space, until at last the king said, “Darby, Darby O’Gill, I’ve a good mind

to, – yes, I will. See here, I’ll give

ye anny three wishes ye’ll be afther makin’ this night, barrin’ only riches.

Now mind what I say, Darby, barrin’ only riches.”

A pleased smile came to Darby’s face, as he said, “Well,

then, the furst wish I’ll be afther makin’ is this; that I may be well fixed

an’ as comfortable as Lord Killgoblin is.”

For Lord Killgoblin was the richest man in all the

countryside, and by phrasing his wish thus Darby O’Gill thought he had got

around the king’s injunction in a very clever style. But hardly was his wish uttered than he felt

himself growing smaller and smaller, and being carried away over the tree

tops, till they came to the castle of Lord Killgoblin, and in the presence

of the great man himself. But he didn’t

look at all as he did when he rode to horses and hounds, for tonight he was

wrapped in blankets, his great feet were swathed in bandages, and resting

on a cushion in a great chair in front of him.

With every breath he uttered groans and curses that were horrible to

hear. His servants fled in and out with frightened

faces, seeking alike to avoid his caustic tongue and the stout oaken stick

that he held in his hand.

Darby watched the scene in shocked silence, then he

turned to the king. “Phwat’s the matter

wid him?” he asked.

“Oh, it’s nothing but the gout. All rich men have it.”

“Do ye mane I’d have that turrible pain

in my toe, too, if I’se as well fixed and comfortable as he is?”

“Shure, only you’d have it worse’n he’s got it, because

he’s alus been used to high livin’ an’ you ain’t, an’ you’d overeat right

away in the furst place.”

“Oh, well, then,” said Darby, “I don’t know as I’d

want it. If I’d have to have that turrible

pain in my toe, an’ besides lose me adorably disposition, I guess I don’t

want it. Ye can take that wish back,

King, but I’ll tell you what I do want. I

want to live to be – oh, I don’t know how old I do want to be. Fact is, I don’t ivir want to die. I’m afraid to die. I’d just like to go on livin’ in this jolly

old warld, for iver and iver!”

Once again they took up their journeying until they

came to the Black Forest, and to the little cottage where lived old Daniel

Delaney, and his good wife, Julia. Almost

five score years had passed over their

heads, and for almost four score they had lived together as

man and wife. A large family of children

had romped through the little cottage. but, one by one, all had passed to

the Great Beyond, and last year, word have come that little Danny, the youngest

and best loved of all, had died in far-off America.

So tonight, Daniel Delaney and his good wife, Julia sat alone by their

dying fire, with none to bear them company, almost deaf, almost blind, almost

helpless with age, the objects of county care, and the occasional kindness

of oft-forgetful neighbors. These things

passed through Darby’s mind, as he saw them sitting there., and then he heard

old Daniel begin to speak in the quivering tones of age. “Julia, Mavourneen, did yez mind how little

Danny used to say – why, where’s Danny? ...

Oh! I mind now...he’s gone, ain’t he Julia? ...

They’re all gone, ain’t they, Julia?

... An’ of all our own kith and kin, there’s none

left alaive, save you an’ me. An’ there’s

nobody cares aught fir us, save each other, and even Death itself won’t come

anigh us to set us free, an’ oh, Julia, lass, it’s so weary an’ tired that

I grow of the waitin’.”

And then he began to cry, as old men will, and old

Julia began to comfort him, as old wives always have, and always must. “Thar, thar, now Daniel, don’t ye be a cryin’,

an’ a takin’ on that way anny more. Instead

o’ feelin’ so bad, let’s just count over how good the Lord has been to us,

for he’s taken them away out of the world, that we loved and cherished, till

taint goin’ to be no trouble at all to lave it, Daniel, no trouble at all.

An’ then He’s filled Heaven so full o’ them we love, that it’s goin’

to be jest a pleasure to go to ‘em, Daniel, jest a pleasure.

Thar, thar now, lad, don’t ye be a feelin’ bad anny more.”

And Darby O’Gill turned tear-filled eyes to the King,

as he said, “O King! Does ye mane it?

Does ye mane that the time would iver come when Bridget and I wad be

sittin’ alone that way, wid all our friends an’ the children gone?

When the only blessin’s we could count, wad be an empty earth, an’

a full heaven, an’ this death, that I fear so much, would be my last and greatest

friend?”

And the King said, “Aye, Darby O’Gill, only it will

be worse for you, for it’s written in the books that Bridget and the children

shall all pass over ahead of you, and you’ll be waitin’ this side of the river

all alone.”

“O well, then, I don’t want it! Why, King, ye know that’s a wish I wouldn’t want

at all. Yez can take it back, – I don’t

want it, I don’t want it! But I’ll

tell ye one thing I do want, an’ it ain’t so very much aither, if only I can

think to say it right. I want to be

happy, an’ that’s all I’ll ask. I want

to be perfectly happy.”

“Oh, well, that’s easy,” said the king.

So once again they took up their journeying, until

they came back to the little village, close by Darby’s own home, and paused

by the house of the smithy. There the

king motioned to Darby to go down thro’ a little alley, and look thro’ the

windows of a hovel, that stood in the rear.

But Darby O’Gill had grown wise by his evening’s experiences, and he

hesitated long, and held back, until at last, urged on by the friendly hand

of the king, he went near, and looked thro’ the windows of the little hovel. As soon as his eyes became accustomed to the

half darkness, he made out the face of Tom, the smithy’s son. He had been an idiot from the day of his birth,

and all the eighteen years of his life, he had lived confused in that little

hovel, more like a beast, than like a human being. But tonight, because it was the night when the

fairy folk walk abroad in Ireland, and all hearts are kind,

fresh straw had been thrown in for his bed, and by some happy chance, a bit

of bright red calico had been caught in it.

This had caught the poor fool’s eye.

He had caught it up in his silly hands, turning it back and forth in

the dying light, and was laughing and gibbering to it in foolish glee. It was the only bit of color in all that poor

fool’s life.

And for the third time that night, Darby O’Gill turned

stricken eyes to the king as he said, “O King, does ye mane it? Is that the only way to be a perfectly happy

man in life, to be a fool, an’ not to know it?”

And the king answered, “Aye, Darby, it’s the only way

I know.”

“O well then, I don’t want that ayther. I’ll tell ye, King, I guess I’ve lost the three

wishes that ye gave me the night, but I’ve larned the lesson ye wanted me

to larn. I’ve larned the lesson o’

content. I’m goin’ home the night,

an’ as long as Bridget and the childer are spared to me, as long as I’ve a

sup to eat, and a bit to dhrink, an’ a roof-tree over my head, ye’ll never

find Darby O’Gill to complain o’ ought, or to wish for more.”

As the king bade him goodnight, and flew away over

the treetops, Darby O’Gill heard him singing “The Song of Content.” It’s a little song that all the good people

of Ireland know and love well.

“If you’ve mate, when you’re hungry,

An’ dhrink, when you’re dry,

Not too old when you marry,

Nor too young when ye die,

Then go happy, go lucky, go lucky, go happy,

Go happy, go lucky, goodbye, goodbye.

Go happy, go lucky, goodbye, goodbye.”

But I can speak to you as a true prophet this evening,

that Darby O’Gill had not found the true secret of happiness, for truest happiness

does not consist merely in counting over the good things that life has given

us, – even in taking too much pride and self congratulation in our own sup

to eat, and a bit to drink, or even in our own loved ones gathered around

us, but it is rather found in sharing our good with another’s need, and I

want to bring you in closing another little story, – this time a true story

that also comes to us from the British Isles.

An American tourist was making a tramping trip, thro’

England. One day his way led him up a long and dusty

hill. The way was long, the hill was

steep, and the dust was exceeding deep. Half

way up the hill he paused to catch his breath, and his attention was held

by a little sign that was painted, and set close beside the roadway.

It read: “Follow the path to the left, There’s a cool spring just down

the hill.” So he followed the little path, until he came

to the little spring, where it bubbled out from among the rocks, all cool

and clear, and silver sweet. A bright

tin dipper hung there, so he drank at the springside, and refreshed himself,

then turning about he saw a bench and on it a basket of apples, all green

and gold and rosy red, and another little sign which said, “Sit down and rest,

and help yourself.”

As he ate he wondered what sort of a fairy land this

might be into which he had come, so when he finished he made his way to a

little cottage, whose roof he had seen among the orchard trees. There he found a quaint old English couple,

and prevailed upon them to tell him their story.

A simple little story it was, too, for youth and happiness

had been theirs, and high hope that they might go out, hand in hand, to be

of service to the world. But one by

one, other duties seemed to come to them.

First an old father and mother whose faltering foot must be guided

down thro’ the valley of the shadow; then a widowed sister who came to their

care, and after she was gone, her orphan children to be brought up and educated. One by one, all these duties had been assumed

and discharged, and at last they found themselves free to go out on that long

dreamed of journey of helpfulness to the world.

Then for the first time they looked upon one another

with startled eyes, for never before had they realized that time was creeping

upon them apace; the snow of many winters lay white on their foreheads; that

they were old, – aye, old and poor, with nothing left to them save the little

farm on the hillside. But at that,

the little farm was theirs, and the cooling spring, and the goodly orchard,

and these they determined to share with the chance traveler who came up that

long and dusty way. So the little signs

were painted, the bright tin dipper hung, and every day, in orchard season

a basket of fresh gathered fruit found its way to the spring-side.

A simple little story, simply told, and you and I might

never have heard it had it not been that the chance traveler that day was

our own American poet, Sam Walter Foss, and he has immortalized the loving

service of the quaint old English couple in a little poem, which I want to

leave with you tonight, as my goodnight wish for your life, and for mine:

“There are hermit souls that live withdrawn

In the peace of their self-content;

There are souls like stars that dwell apart,

In a fellowless firmament.

There are pioneer souls that blaze the way

Where highways never ran;

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

Let me live in a house by the side of the road,

Where the race of men go by, –

The men who are good and the men who are bad, –

As good, and as bad, as I.

I would not sit in the scorner's seat.

Nor hurl the cynic’s ban –

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.

I see from my house by the side of the road,

By the side of the highway of life,

The men who press on, with the vigor of hope,

And the men who are worn in the strife.

And I turn not away from their sighs, or their tears,

Both parts of an Infinite plan.

For I live in a house by the side of the road,

And I am a friend to man.

I know there are brook-gladdened meadows beyond,

And mountains of wearisome height, –

That the road passes on, thro’ the long afternoon,

And stretches away to the night.

But still I rejoice when the trav’lers rejoice,

And weep with the strangers that moan.

Nor live in my house by the side of the road,

Like one that dwelleth alone.

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

Where the race of men go by.

They are good, – they are bad, –

They are weak, – they are strong, –

Wise, – foolish – so am I.

Then why should I sit in the scorner’s seat,

Or hurl the cynic’s ban?

Let me live in a house by the side of the road

And be a friend to man.”

I

want to bring you in contrast, and in closing, another little legend, which

comes to us from the Italians, the legend of Saint Michal (Michal), the cobbler.

St. Michal lived in the lower streets of Rome,

and among those who knew him he was counted a very queer character, for while

he had little of this world’s goods, yet he so gladly shared with whoever

came to him in need, that the word had gone out among all the poor and outcast

everywhere, that if they could but reach St. Michal’s door, they would receive

help, and refreshment and comfort.

St. Michal was a goodly man, and often as he cobbled

on his shoes he meditated on the word of God, and his nightly prayer was this,

that he might live worthily, so that sometime he might see the King, in all

His beauty face to face.

One night as he lay upon his bed, St. Michal had a

dream. In it, he seemed to see his

risen Lord appear before him and say: “Michal, Michal, arise and make ready

thy house for tomorrow I must come and dine with thee.”

St. Michal awoke and perceived that he had had a vision,

not a dream, so while it was yet dark of the morning, he rose and lit his

candle, and began to set his house in readiness for his Great Guest. He paused only to prepare for a hasty breakfast

for himself, but just as he was about to sit down and eat, he heard a little

child crying in the street without. He

went out to see perchance what the trouble might be, and there he found a

little boy of perhaps four years of age, who had lost his way. St. Michal brought him in, fed him the porridge

he had prepared for his own breakfast, and then, when the little one had eaten

he took him in his arms, and started out thro’ the streets of the city.

For hours they wandered up and down, until a glad cry of “Oh, there’s

home” the little one leaped from his arms and disappeared down a side street.

St. Michal hurried homeward on frightened feet, fearful,

lest, in his absence, his Great Guest might have come, but everything in the

little cottage was just as he had left it.

Thro’ the remaining hours of the morning, St. Michal

labored tirelessly, and at noontime a goodly meal was set forth upon his table

for he said, “It may be at the noontide, my Lord will come.” And just at the noontime hour, he heard a hand