Childhood

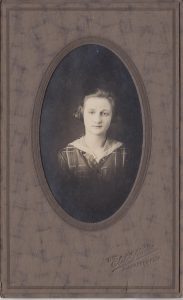

Mildred Augustine Wirt Benson was born to Dr. J.L. and Lillian (Matteson) Augustine in Ladora, Iowa on July 10, 1905. She was the younger of two children; her brother Melville Augustine was seven years older. Perhaps it was her older brother who influenced her interests at an early age: athletic pursuits and adventures, whether in real life or on the pages of a book, appealed to her more than playing with dolls. She was also quite musical; newspaper articles praise her xylophone performances at community functions.

From a very early age, Mildred Augustine was determined to be an author. She later recalled proclaiming “to anyone who would listen” that “‘when I grow up I’m going to be a GREAT writer.'” Her first published work was a short story titled “The Courtesy” that appeared in the children’s publication, St. Nicholas Magazine in June 1919, when she was just thirteen years old. Several more of her writings were to follow in both that magazine and in Lutheran Young Folks. These publications would eventually help fund her college education.

In 1922, Mildred received her Ladora High School diploma alongside her three classmates. It was an exciting time, marked with a baccalaureate, a class performance of the comedy Bashful Mr. Bobbs in the Ladora Opera House, and the graduation ceremony. The local newspaper noted that “the earnest wish of all is that these four young people will so conduct themselves in the wider fields of life that they will bring honor to themselves and to old Ladora High.”

Mildred would go on to do just that.

College Years

The fall after graduating high school, Mildred Augustine enrolled at the State University of Iowa (now known as the University of Iowa). Always open to new experiences, she soon took advantage of the diverse clubs and activities now available to her. She continued writing, joining the Hawkeye Yearbook staff as an editor and The Daily Iowan, the college newspaper. She was elected into the journalism sorority Theta Sigma Phi and other groups of writers. She was also a part of the Cosmopolitan Club, a group that celebrated friendships across cultures.

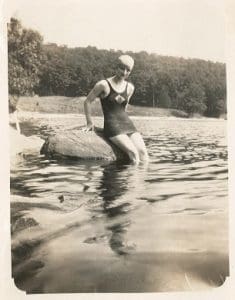

Mildred remained an athlete throughout her college years. As a freshman, she participated in soccer and track. She also joined the basketball team and excelled in both swimming and diving. She became a Seals Club member and a championship diver; a photo of her beautiful swan dive into the Iowa River is often reproduced and has become one of the Iowa Women’s Archives’ iconic images.

Engaged in so many activities, her college career went by quickly. She graduated in just three years, earning a college degree in English in June 1925. She spent the following year working for the Clinton (Iowa) Herald as a reporter. There she wrote mainly society pieces. In the fall of 1926, after visiting Europe and New York, Mildred returned to the State University of Iowa (SUI) to enroll as a graduate student in the journalism program. In June 1927, she was the first person to receive a master’s degree in journalism from the University.

The Stratemeyer Syndicate

In the year between graduating from SUI and returning for a master’s degree, Mildred Augustine visited New York with the dream of becoming a writer. While this trip did not end with her finding a job, she did meet Edward Stratemeyer, the owner of Stratemeyer Syndicate. The syndicate was known for publishing many popular juvenile series, such as the Bobbsey Twins and The Hardy Boys. The Syndicate was able to produce mass quantities of books with the help of ghost writers. The ghost writers were given a brief plot outline and chapter summaries of no more than two or three pages from which they wrote a full book. They received a flat fee for their work, and in exchange signed away all rights.

After Mildred returned to Iowa, Stratemeyer contacted her with the opportunity to write a novel in the Ruth Fielding series under the pseudonym Alice B. Emerson. Writing Ruth Fielding and Her Great Scenario was a struggle for her. Mildred later recalled that the character of Ruth “fought me on every page” as she wrote the book at her childhood home in Ladora. The final 208-page manuscript was well received by Stratemeyer, and the book was published in 1927 by Cupples & Leon Company. Augustine wrote her second manuscript, Ruth Fielding at Cameron Hall, when she was supposed to be working on her master’s thesis at SUI. “I was the only person in the journalism graduate school, so I figured they’d have to pass me,” she admitted decades later. The book was published in 1928.

Stratemeyer was pleased with Mildred Augustine’s work. In 1929, Stratemeyer offered her the chance to work on a new series that focused on a teenage sleuth named Nancy Drew. He sent her the outlines for the first three books: The Secret of the Old Clock, The Hidden Staircase, and The Bungalow Mystery. With the plots in hand, Mildred set to work developing a character that was bold, brave, and clever. Although Stratemeyer initially had concerns that Nancy Drew was “much too flip,” he sent the manuscripts to Grosset & Dunlap for publication. By April 1930, the books were on store shelves and proved to be so popular the publishing company requested more titles. Sadly, Stratemeyer died twelve days after the release of the series, but Mildred was kept on as Nancy Drew’s ghost writer. She wrote 23 of the first 30 books of the series under the Syndicate-chosen pseudonym Carolyn Keene.

Through the 1930’s and 1940’s, she continued to write fiction for children and young adults under her own name, her own pseudonyms, and collective pseudonyms owned by Stratemeyer Syndicate. She wrote over a hundred novels, many of which were sold along with any royalty rights to the Syndicate for a flat fee ranging from $85-$250.

Family Life

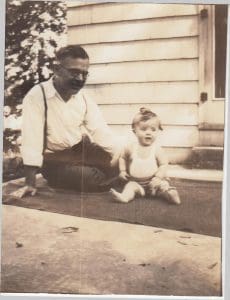

While on the SUI campus, Mildred Augustine met Asa Alvin Wirt (1886-1947), a telegraph operator for the Associated Press. They married in Chicago on March 4, 1928 and moved to Cleveland, Ohio. Asa worked nights at the Associated Press, while Mildred wrote her books on a typewriter that sat on an overturned orange crate. The two enjoyed travelling; photographs show them camping, hiking, and fishing together.

In 1936, their daughter Margaret Joan “Peggy” Wirt was born. In a letter dated January 1937 to the Stratemeyer Syndicate, Mildred announced, “… early in November I gave birth to a blue-eyed, red headed baby girl.” Shortly after Peggy was born, Asa was transferred by the Associated Press from Cleveland to Toledo and the family moved.

Neither the new status of motherhood nor the change in location deterred Mildred from writing. She continued on as a ghost writer for the Syndicate, adding body to the outlines of books for the Nancy Drew, Dana Girls, and Kay Tracey mystery series. She began creating her own series and characters, such as the brave aviator Ruth Darrow and the intrepid newspaper reporter Penny Parker, a girl sleuth Mildred preferred over the increasingly popular Nancy Drew. She submitted writings to magazines as well, publishing numerous stories and articles in St. Nicholas Magazine, Lutheran Young Folks, Our Boys and Girls, and Calling All Girls, using both her own name and pseudonyms.

In late 1940, Asa suffered a stroke. This would be the first of a series of strokes that would limit him the rest of his life. He took a leave of absence from the Associated Press in the summer of 1941 and worked sporadically over the next two years. When his illness took a turn for the worse in 1943, he left the Associated Press entirely.

The next several years were a struggle for the family. Lillian Augustine, Mildred’s mother, came to stay and help take care of Asa and young Peggy so Mildred could work. She was able to find a temporary position writing publicity pieces at the Toledo Community Chest in the summer of 1944 and that fall, after multiple applications, she was hired at the Toledo Times as a news reporter. With World War II raging across the other side of the ocean and men called into service, male reporters were scarce. The Times took on female reporters for the first time. As Mildred later recounted, “[The editor] said ‘As soon as the war is over, I want you to understand you will be the first one to be fired.’ I ran scared for about at least 49 1/2 years.” Nonetheless, she was given a permanent position after the war ended. She also continued to write books for the Syndicate. She pulled her Underwood typewriter into the bedroom so when she came home from work she could type while at Asa’s bedside. After a seven-year struggle with his debilitating illness, Asa died in June 1947.

Three years later in 1950 Mildred married George A. Benson (1889-1959), an editor at the Times. It was a second marriage for both; George’s first wife had died in 1948. George, like Mildred, loved to write. After graduating from high school, he started at the Grand Forks (ND) Herald and worked his way up to the position of managing editor. He later became the head of the Washington, D.C. bureau of the Minneapolis Journal. George Benson was passionate about politics and the English language. He enjoyed cooking for stepdaughter Peggy while Mildred stayed at the office to finish up her work as a courthouse reporter for the Times. She also wrote features for the Toledo Blade.

These were happy years. George and Mildred Benson played golf together and went dancing. They also traveled, touring Central America. In 1959, the night before the couple planned to leave for a trip to Puerto Rico, George died unexpectedly from a stroke. Mildred would never marry again.

New Adventures

In the 1960’s, Mildred Wirt Benson faced a series of personal and professional changes in her life. Now widowed with a grown child, she no longer had family depending on her or waiting for her at home. In an effort to produce more manuscripts and exert more control over the writing, the Stratemeyer Syndicate had changed its policies in regards to ghost writers and stopped sending Mildred work. Her own series were also facing setbacks. One was the abrupt end of the Cub Scouts, Girl Scouts, and Boy Scouts series after the Girls Scouts organization objected to her using their name in written works. After decades of being a prolific author, at one point even writing thirteen books in one year, Mildred Benson was done writing fiction.

Instead, she focused on her career in journalism, transitioning to a full time position at the Toledo Blade when the Times went out of business in the 1970’s. When a publisher asked around that time if she would consider writing juvenile books again. Mildred ultimately and regretfully declined, stating that “. . . the teenagers for whom I wrote lived in a world far removed from drugs, abortion, divorce, and racial clash . . . Any character I might create would never be attuned to today’s social problems.” Perhaps not, but those teenagers might have appreciated the adventures Mildred pursued.

Mildred had always loved to travel. She had a particular fascination with the Mayan ruins in Central America, so she began to charter bush pilots to visit less accessible archaeological digs. She canoed down the Usumacinta River to Yaxchilan on a three-day trip with native guides. “I used to hang my hammock in Mayan temples and once, when no other shelter was available, I hung it in a corn crib. Those were my more adventurous days,” Mildred later told an interviewer. On one trip to Guatemala, she was briefly kidnapped, much like a character in one of her books.

After her experiences with bush pilots, Mildred decided to take flying lessons. She earned her commercial pilot’s license in 1964 at the age of fifty-nine. This led to her writing a weekly aviation column titled “Happy Landings” for the Toledo Blade. Her love for flying knew no bounds. In January 1986, she applied to be in NASA’s journalist-in-space program. The explosion of the Challenger a few weeks later put a quick end to the program. It was not, however, the end of her travels.

A Final Chapter

The 1990’s brought new opportunities for Mildred Wirt Benson. She started a weekly column for the Toledo Blade. Titled “On the Go”, the column became a platform for Mildred to share about her continuing pursuits in golf and aviation and her opinions on the changing world. She also featured local senior citizens who remained active in their communities and with their hobbies. Mildred herself was appearing more frequently in the newspaper as awareness of her role in the creation of Nancy Drew grew.

A decade earlier in 1980, she had been called to the witness stand in a case between the Grosset & Dunlap publishing company and the Stratemeyer Syndicate. The Syndicate, hoping to make more money, had signed away all future titles to the publisher Simon & Schuster. This new contract also allowed Simon & Schuster to publish paperback editions of both old and new books, while Grosset & Dunlap only published in hardback. Grosset & Dunlap fought back, arguing that this arrangement was a breach of contract and that the Syndicate didn’t truly own work written by ghost writers. According to Grosset & Dunlap, this work included the Nancy Drew Mystery Stories. It was a disputed claim: Edward Stratemeyer’s daughter and senior partner of the Syndicate, Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, had publicly declared herself the sole author of the Nancy Drew series. She told reporters she began penning the series after finding the first three outlines on her late father’s desk. When Harriet was introduced to Grosset & Dunlap’s witness, Mildred Wirt Benson, her surprised response was “I thought you were dead.”

Grosset & Dunlap lost the court case, and although the evidence had identified Mildred as the original author, there was very little fanfare. That didn’t come until years later after Susan Redfern, a journalism school secretary at the University of Iowa School of Journalism and Mass Communication, discovered an alumni file labelled Mildred Augustine. As research into Mildred’s life commenced, staff members pushed for her nomination into the journalism school’s alumni Hall of Fame. She was inducted in 1991. One journalism professor, Carolyn Stewart Dyer, led a committee to organize the first ever Nancy Drew Conference in 1993. Mildred Wirt Benson was an honored guest that made national headlines. The original Carolyn Keene was finally unveiled.

Mildred Wirt Benson speaks to the press at the Nancy Drew Conference, April 17, 1993. Image taken by John Kimmich.

After the Conference, Mildred was flooded with awards and recognition for her writing career. In 1993, she was inducted into the Ohio Women’s Hall of Fame. The University of Iowa honored her with its Distinguished Alumni Award in June 1994. That August, she was inducted into the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame. She was the first recipient of Toledo Blade’s Lifetime Achievement Award for an Outstanding Journalist in 1998. Three years later, Mildred was awarded with an Edgar Allan Poe Special Award from the Mystery Writers of America for her work on Nancy Drew.

Amidst the accolades and daily life, Mildred Wirt Benson was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1997. Although she never smoked herself, her decades spent in a workroom alongside journalists who did had taken an effect. She started working less days in the week, but continued on with her column “On the Go”. On May 28, 2002, Mildred went to turn in her last piece, an article about Carnegie libraries, and left for home feeling ill. She was taken to the Toledo Hospital hours later, where she passed peacefully at the age of ninety-seven.

A Note on Sources

The biographical information on this site is drawn from:

Mildred Augustine Wirt Benson papers, Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Libraries

Mildred Wirt Benson, “The Ghost of Ladora,” Books at Iowa 19 (November 1973): 24-29

Carolyn Stewart Dyer and Nancy Tillman Romalov, Rediscovering Nancy Drew (University of Iowa Press, 1995)

Jennifer Fisher, “Mildred Wirt Benson & Carolyn Keene: A Mystery Revealed,” Firsts The Book Collector’s Magazine (December 2006): 18-31

Geoffrey S. Lapin, “The Ghost of Nancy Drew,” Books at Iowa 50 (April 1989): 8-27

Frank Paluka, “Mildred A. Wirt,” Iowa Authors (1967): 197-208

Melanie Rehak, Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her (Harcourt, Inc., 2005)

Nancy Drew Collection papers, Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Libraries.

Julie K. Rubini, Missing Millie Benson: The Secret Case of the Nancy Drew Ghostwriter and Journalist (Ohio University Press, 2015)

Mark Zaborney, “Thanks for the 50 Years, Millie,” Toledo Blade (September 1994)

“The Adventurous Millie Benson,” The People’s Voice 3, no. 4 (December 1974)

Quotations

“When I grow up”: Mildred Wirt Benson, “The Ghost of Ladora,” Books at Iowa (November 1973): 24-29

“Fought me on every page”: Mildred Wirt Benson, “The Ghost of Ladora,” Books at Iowa (November 1973): 24-29

“I was the only person”: Carolyn Dyer, “Blowing Carolyn’s Cover” original draft. Articles about Mildred Benson, 1983-2002. Mildred Wirt Benson. Nancy Drew Collection papers, Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Libraries.

“Much too flip”: Mildred Wirt Benson, “The Ghost of Ladora,” Books at Iowa (November 1973): 24-29

“Early in November”: Melanie Rehak, Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her: 183

“[The editor] said”: Mark Zaborney, “Thanks for the 50 Years, Millie,” Toledo Blade, September 17, 1994

“The teens for whom I wrote”: Mildred Wirt Benson, “The Ghost of Ladora,” Books at Iowa (November 1973): 24-29

“I used to hang my hammock”: “The Adventurous Millie Benson,” The People’s Voice 3, no. 4 (December 1974)

“I thought you were dead”: Geoffrey S. Lapin, “The Ghost of Nancy Drew,” Books at Iowa 50 (April 1989): 8-27