The University of Iowa Libraries

Special Collections and University Archives

Special Collections

EVELYN HARTER

From Books at Iowa 41 (November 1984)

Copyright: The University of Iowa

Robert Graves has said that he raises dogs in order to keep cats, his way of stating the conflict between livelihood and literary accomplishment. It was one of the subjects batted about by a group of students at Iowa during the mid-twenties, when we occasionally gathered around a table in a private room in Youde's boardinghouse in Iowa City. [1]

Along with our freewheeling criticism of famous writers, of Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson (Hemingway's sun had not yet risen), we excoriated Paul Elmer More and Irving Babbitt, quoted H. L. Mencken with glee, admired Ruth Suckow, and talked of our own writing-how were we to do it while earning a living? Was it necessary to starve in an attic, to deny the experiences of marriage and children, to renounce creature comforts and foreign travel in order to write the great and true work we felt within us? Was it true, as Yeats said,

The intellect of man is forced to choose

perfection of the life or of the work.

One answer was the teaching profession with its long vacations, but with it came the fear that it might restrict our imaginations, that we might not find our richest material in academe. There were quotidian compromises-bricklaying or waiting on table by day in order to write without distraction at night. Eventually one of us went into subsistence farming and carpentry, others into journalism and teaching. Part of my own answer was to produce books for other writers in order to write my own.

Several of the students with elbows on the table at Youde's were earning their way through college and were already familiar with the harsh demands of economic survival. All of us were opinionated, argumentative, occasionally witty as we inveighed against what we feared were the terms of the literary life while still feeling that we had a future in writing.

One subject of talk was the starting of a university literary magazine. This was backed by the would-be writers and also had the encouragement and support of some nonwriters -- Agnes Kelleher, Paul Dwyer, Harry Stevenson -- and it was endorsed by the six campus literary societies.

As editor of the Iowa Literary Magazine for 1924-25 1 became acquainted with many students interested in writing. There were 57 contributors in the first five issues. Reading the magazines now reveals a lot that was amateurish, but also much that held promise. Douglas Branch wrote a sophisticated piece about cheeses at a time when most of us had never heard of anything but rat-trap and cottage cheese. Buel Beems contributed an imaginative essay on "The Origin of Red Hair," and Paul Corey was represented by several good short stories. There was much excellent verse.

More of those who contributed to the magazine might have gone on with writing but for the lack of feedback and appreciation. The publishing prospect is better now for the presence of hundreds of little magazines printing "creative writing," though many writers are uncomfortable with that word, which seems presumptuous and blown up. People who use it seek to distinguish between imaginative writing and reporting. In a profession which names things, we do badly; fiction and nonfiction are awkward terms, even in the marketplace. If nonfiction (biographies, memoirs, etc.) is named for what it isn't, then poems, essays, plays might well be called non-nonfiction.

In the decades after the twenties students at Iowa had the encouragement of Paul Engle's Writers' Workshop which blossomed after World War 11, and again when Iowa introduced a startling innovation, giving advanced degrees for fiction.

Although I did not always choose notable courses at Iowa -- not those under Sam Sloan and Hardin Craig and Edwin Ford Piper -- by luck or precognition, I did sign up for Charles Weller's "Printing and Engraving" -- of this more later. Very valuable to me was John Frederick's course in "Contemporary American Literature." Suddenly we found that what this man standing at the front of the room was saying, often in a sad voice, sometimes spiked with humor, was immensely relevant to our needs. He admired good writing and encouraged the faintest manifestations of it in his pupils. We felt that he gave us a glimpse of a world to which we belonged. Forty years later I happened to ask a young relation enrolled at Iowa, "Who is the outstanding teacher you have there?" and she answered without hesitation, "There's one -- he's quite old. He's the best. John Frederick." This was in the time when he had returned to Iowa after years at Northwestern and Notre Dame. [2]

In 1925 New York seemed the place of maximum opportunity, of challenging associations, of necessary risk. Buel Beems said we were drawn there like young artists going down to Florence from the hills of Tuscany in the Renaissance.

After graduation I set off for Gotham with Ruth Middaugh, a friend who had been on the board of the literary magazine. In New York we found a room in an apartment house near Columbia University. Getting a job proved easier than I expected, for I had a letter from John Frederick to John Hall Wheelock on the staff of Charles Scribner's Sons. I did not know at that time what a good poet he was, that he would spend 47 years working with authors at Scribner's while continuing to write his grave, musical poetry, his salutes to "dark joy."

He told me that there was an opening as secretary to the advertising manager of Scribner's Magazine at $22 a week. I decided this would do for a beginning. I found that my typing and shorthand were just barely good enough. I was startled to see that the files for the advertising department were labeled New York City, New York State, New England, and the West.

That was a year of intoxication with New York. We moved down from Columbia to Greenwich Village in search of what was in those days called a Bohemian atmosphere. There we didn't live in an attic, but in a room with no heat except a fireplace stoked with coal; the landlady started the fire before we came home in the evening, and we banked it for the night. It was a year of making trips of veneration, literary pilgrimages to the former homes of famous authors: Henry James in Washington Square, Poe's cottage in Fordham, Edna St. Vincent Millay's little house close by us. Willa Cather lived a few doors away and was sometimes to be seen prosaically buying vegetables in a store on Bank Street.

Partway through that year the advertising manager left, and I became secretary to his successor, C. E. Hooper (later famous for his Hooper ratings), who thought I had a future in business. But I knew that in the terms of Yeats's dictum I was making a decision by default. When summer and vacation time arrived I decided to accept an invitation made by John and Esther Frederick when I was still in Iowa City -- that I visit them in Glennie, a small town in the northern part of the southern peninsula of Michigan. The Fredericks had bought land and spent summers in Glennie after the Clark F. Ansleys -- he had been dean of the College of Fine Arts at Iowa -- had vacationed there in the cut-over country. [3]

I sent a telegram to the Fredericks saying I was coming, and I arrived before the telegram was delivered. But they were cordial. There was a serenity and thoughtfulness about Esther Frederick and a probing imagination in John that made for good table talk. After I was there a week or so they told me that a teacher was needed for a log school a few miles away. Would I want to take it on? The salary was $450 for the school year. Well, perhaps I could write better, after all, in the clear air and isolation of a Michigan winter in the country.

I stayed. A neighboring farmer who was also a good carpenter built a one-room tar paper cabin on the shores of a lake where I could get water, chasing the snakes off the raft in summer and breaking through the ice to get water in the winter. My cabin was something more than an eighth of a mile from the Fredericks' house. No artist's garret but solitude enow.

I had seven pupils, one in each grade. Although I had no training for teaching and little vocation, I did manage to teach the youngest child to read and the oldest to get through his county exams. When a big snow came I drove one of the Frederick horses hitched to a wagon, starting out with the two Frederick boys and picking up another child on the way. On both sides of the road through the jack pines there would be a fine exhibition of calligraphy made by the feet of birds and small animals on the perfect white snow.

When we arrived the oldest pupil unharnessed the horse and put it in the shed, another got the fire going in the center stove, another primed the pump and drew water, and when all was ready we rang the school bell and started the first class. At recess time in good weather we played alleyover, throwing the ball over the schoolhouse.

My only writing during this period was a review for John Frederick's Midland and several for the Chicago Daily News which had lately acquired a new book review editor, Robert O. Ballou, of whom I was to know much more later.

That year in Michigan had a Currier and Ives idyllic quality, but when the school year was over I resumed my zig-zag course, returning to New York, leaving my tar paper cabin to become a place to store dynamite for stump blowing.

When I returned to New York Ruth Suckow moved in with me for a short period, having been dispossessed by a fire in her own apartment. Here was a committed writer to whom I could talk, who was open and serious and also had more sense of humor than people gave her credit for.

At this time I had the idea of becoming a stewardess in order to "gather material," but I was saved from myself by the steamship companies who wanted no such inexperienced gatherer. Iowa classmates Paul Corey and Eddie Baker were working on the fourteenth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and reported that the management was still hiring. I applied and was given a job in the production department. Many of the articles were written in England, dispatched to New York for checking and forwarded by me to R. R. Donnelley in Chicago for composition and printing.

During this year life was far too exciting to allow much time for the slow, painstaking act of writing. I did often get up at five o'clock to write before I went to work, but my product followed a direct trajectory from the typewriter to the waste basket. I might have stayed on at the Britannica except that one summer day I had a letter from Robert Ballou saying that he was coming east to undertake design and production of books for a new publishing house to be called Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith. Cape was a famous English publisher and Smith had been chief editor at Harcourt Brace and Company.

We met over lunch and Ballou offered me the job of secretary to the production department. This was what I had been hoping for. I had no wish to work in the editorial department where I might possibly confuse my fine original ideas with those of the manuscripts coming in. Nonetheless I wanted to be in the ambiance of a publishing house. The new firm occupied a three-story old brownstone house at 139 East 46th Street, between Lexington and Third avenues. The staff could not have exceeded ten people, including the salesmen. After getting the venture started Jonathan Cape went back to London, leaving the office to be run by Harrison Smith and Louise Bonino, whom Harrison Smith (Hal) had brought from Harcourt Brace to be in charge of publicity, promotion, contracts and rights, and in fact to become the heart of the firm.

The reception room, telephone desk, and sales departments were on the main floor, editorial offices on the second and third floors. Our production department was properly situated in the basement, the former kitchen.

From the beginning the walls of the office of Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith vibrated with expectation and an esprit de corps such as I have not encountered elsewhere. There was a handsome curving staircase which rattled when employees ran up and down. The laughter of Louise Bonino floated through the house. All rejoiced when a piece of good news was received, such as a front-page review of one of our books in the Times or the Herald Tribune book sections, or we had a Book-of-the-Month selection, or a 500-copy order from a wholesaler. There was little ceremony or restraint between employees at different levels of responsibility. If a party was given for an author the underlings were included. The tone of the house was informal, the working hours not completely rigid, but visitors said at least we were "not as undisciplined as the house of Liveright."

In the beginning I typed letters and print orders, answered the phone, did the filing, but as time went on Bob Ballou became more and more involved with the management of the business and began leaving production to me. This is where my little course in "Printing and Engraving" at Iowa stood me in good stead. I found that Charles Weller had given me the fundamentals of good composition and presswork, so that I was not unfamiliar with the ground. With Bob Ballou's coaching I was soon doing almost everything in the design and production department. I learned fast because I had to.

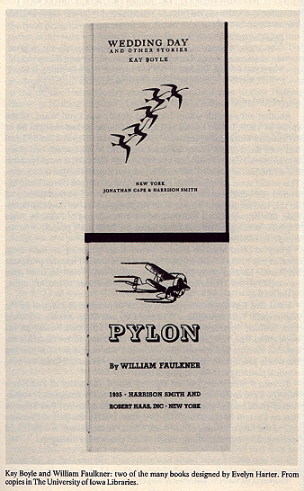

Under these circumstances I corresponded with most of the authors and met many of them who came to the office. When I arrived at Cape and Smith The Sound and the Fury was already in work, designed by Robert Ballou. Although I had not seen any of Faulkner's work until then, I can honestly say that when I read the first paragraph in proof, the beginning of Benjy's soliloquy, I knew I was in the presence of something remarkable. As it turned out, I was to design and produce Faulkner's work beginning with As 1 Lay Dying, through Sanctuary, Light in August, Pylon, These Thirteen, Dr. Martino, A Green Bough, and Absalom, Absalom. [4]

Under these circumstances I corresponded with most of the authors and met many of them who came to the office. When I arrived at Cape and Smith The Sound and the Fury was already in work, designed by Robert Ballou. Although I had not seen any of Faulkner's work until then, I can honestly say that when I read the first paragraph in proof, the beginning of Benjy's soliloquy, I knew I was in the presence of something remarkable. As it turned out, I was to design and produce Faulkner's work beginning with As 1 Lay Dying, through Sanctuary, Light in August, Pylon, These Thirteen, Dr. Martino, A Green Bough, and Absalom, Absalom. [4]

Early on I undertook to do a bibliography of Faulkner's work with Kenneth Godfrey, a salesman for the firm. I did gather and write down data about the size of the printings and other production details which later turned out to be valuable for scholars, but I soon decided that I was not the stuff of which bibliographers are made.

Nevertheless over the years I sometimes saved galleys and page proofs of books. This included the galleys on which Faulkner rewrote Sanctuary. Eventually I let the University of Texas have these so that scholars might gain access to them.

People often ask me about Faulkner -- what was he like, what did he say, how did he dress, was he critical of what I did on his books. At rare meetings at my desk or in the editorial offices he was always the Southern gentleman. No drinking or luridly funny stories -- these were for late nights with Hal Smith and other cronies. Often his letters were written neatly in his small hand, as were the first drafts of his manuscripts. He wrote me the following note after I had asked him, at Elmer Adler's request, if he would contribute an account to The Colophon of his experiences in getting into print in a series of that title. As you can see, his humor extended into his correspondence. [5]

Dear Evelyn-

Your note received. I have not forgot about Mr. Adler, but I am still too busy writing the stuff to have time to even wonder myself how and why it gets printed. Tell him the best way I know to get published is to borrow advances from the publisher; then they have to print the stuff.

Bill F

Love to Louise.

Another author with whom I worked closely was Lynd Ward. In the spring of 1929, before I came to Cape and Smith, he had brought 30 or 40 woodcut blocks for a proposed "novel in woodcuts" to Hal Smith. Lynd had seen the work of Franz Masereel and Otto Nuckel which had given him an intense desire to do such a novel himself. Hal said he would publish it if all the blocks could be delivered by August for publication in October. This would seem an impossible goal, but Lynd undertook the task and delivered 109 additional blocks for Gods' Man on time. I worked with Lynd on this and subsequent books: Wild Pilgrimage, another novel in woodcuts, this in two colors; illustrations for a translation of Faust by Alice Raphael; binding labels and frontispiece for Faulkner's poems, A Green Bough; an edition of Frankenstein.

Every so often Maurice Hindus would come bouncing in, back from another trip to the USSR, excited by what then seemed hopeful prospects for Russia; his Humanity Uprooted was selling well. From the front door he would call out "Tovaritch" to the telephone operator, to me, to Louise, to the house.

I watched Kay Boyle emerge as a writer of promise in Plagued by the Nightingale, Year before Last, Wedding Day and Other Stories. I worked with William Spratling on Little Mexico, with Hickman Powell on his book about Bali, The Last Paradise. These and many others made life delightful, even on $45 a week. For this sum I was responsible for running the whole production department with its heavy responsibilities for economical planning and the okaying of bills.

To earn a little more I asked Mildred Smith, the editor of Publishers Weekly, if she could use a column once a month on the design and production of trade books, and she agreed. I wrote this column, "Full Trim: A Bias on Current Bookmaking," for five years. During this period I became one of the first members of the Book Clinic, an organization which held meetings for shop talk among designers and production managers.

David Godine has recently pointed out the remarkable influx of women designers in the sixties and seventies, saying that probably more than half the book designers today are on the distaff side. In 1929 women's participation in this field was limited: Edna Beilenson was a partner with her husband at the Peter Pauper Press; Emily Connor was working with Hal Marchbanks; Jane Grabhorn did several amusing books under her Jumbo Press imprint, and she set type for the Grabhorn shop; Margaret Evans produced elegant small books for Frank Altschul's Overbrook Press. Early in the thirties Helen Gentry came east from California to start Holiday House, publishing children's books excellent in subject matter and typography.

As far as I know I was the only woman in the 1930s doing a complete job of design and production for a trade (non-textbook) house publishing 20 to 30 titles a year. In the fever of getting everything done in time there was always a temptation to cut corners, and sometimes I did; but in my nine years in publishing, ten of my books were included in the annual Fifty Book shows of the American Institute of Graphic Arts.

Strangely enough the thirties, in the middle of the depression, saw the production of better trade books than the decades since. There was concern about using good materials, pleasant typefaces, getting clean presswork. During these years I found myself drawn to the company of designers and printers rather than writers. Perhaps because printers are primarily craftsmen rather than artists, they tend to be more congenial; they have the self-confidence and self-acceptance of the good artisan; they are rarely jealous of each other, admire what is well done, and usually enjoy their competitors' society. Writers are more likely to be loners.

By 1932 all was not well with Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith. The difference in temperament between the two partners was wider than the Atlantic -- Hal's mercurial life-style which appealed to authors versus Jonathan's dogmatism about wholesalers' discounts and advances to writers. The firm was losing money. Jonathan Cape came over, and as the owner of more than 50 percent of the capital stock, he showed the door to Harrison Smith. I will always remember Hal's sleep-walking expression as he came down the curved stairway after this interview.

Robert Ballou was to be the new partner in the firm and he, as well as Cape, urged me to stay on. But what Jonathan might do seemed even less predictable than what Hal had in mind, and when finally Hal decided to start a new firm and invited Louise and me to join, we did.

While Hal's secretary was cleaning out the old files, she called me to ask if I wanted to see some letters from Faulkner she'd turned up. Of course I did, and when I read them I was astounded to find that they had been left in the open file. One letter was about what I think was the first mention of writing As I Lay Dying while "passing coal in a power house" and two were about home chores and deer hunting, but the one that startled me had been written in desperation. It asked Hal for $500 in complete confidentiality because he was going to be married. No question of pregnancy, but "for my honor and sanity -- and I believe in the life of a woman."

The secretary gave me the letters. For a while I wondered what to do with them in order to protect the principals, and finally I put them in my safe deposit box where they stayed for 40 years, unknown to anyone but my husband and myself. By then all the principals had died, and I donated the letters to the Berg Collection, New York Public Library.

Hal took space for his new firm at 17 East 49th Street, hired a bookkeeper, and we published a few books under his imprint until he acquired a new partner, Robert Haas, who had been cofounder with Harry Scherman of the Book-of-the-Month Club. We were joined in a few months by Harriet McLain Robbins who read manuscripts and manned the telephone desk, and by Dorothy Darrow whose help was particularly needed since Milton Glick and I wished to take our honeymoon in Europe.

For once "the work and the life" seemed to be in conjunction. I learned on the very day we announced our engagement to our printing friends at a luncheon meeting of the Biblio-Beef-Eaters that Story, the magazine edited by Whit Burnett and Martha Foley, had accepted my short story, "Forty-Niners Go East," my first published story.

Our marriage was the beginning of a happy partnership in living and in printing. We were never at a loss for conversation because our backgrounds, our friends, and our lingo were the same. Tony's training was better than mine because he had taken his apprenticeship in printing at a press in England and had continued it in Mount Vernon with the Printing House of William Edwin Rudge. This was at a time when Bruce Rogers was working on the design and production of the Boswell Papers. After a year there Tony left to join The Viking Press and stayed for thirty years. During that time Viking and Knopf did much to raise the standards of book production in the United States.

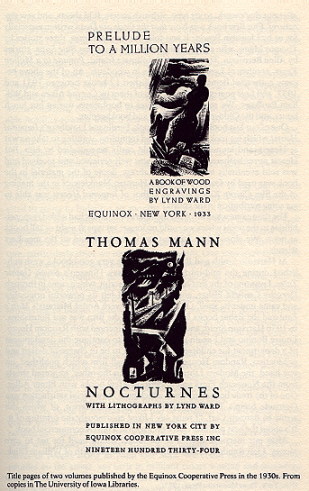

As if life weren't full enough, we joined with a small group to start a private press of our own. While working with Lynd Ward on his novels in woodcuts, I came to know him and his wife, May McNeer, a writer of books for children. When Lynd proposed that with other friends we start a cooperative press to make and publish fine books, doing as much of the work as possible by hand, I welcomed the prospect. Equinox Cooperative Press combined a variety of talents: Lynd and John Heins were artists, Henry Hart (then at Scribner's) was our editor, Mildred and Stanley Oldden were business people who liked books, Belle Rosenbaum was assistant editor of the Herald Tribune Books, Tony and I were designers, and most important, Lew White was an excellent printer who had a shop where we amateurs were allowed to set type by hand. We met at night, after our day's work, to set type, airbrush covers, fold sheets, and sew signatures. Our first book was Now that the Gods are Dead written especially for us by Llewelyn Powys; it was followed by Nocturnes, three stories by Thomas Mann, who signed many copies for us; Three Blue Suits, stories by Aline Bernstein, Thomas Wolfe's intimate friend; Prelude to a Million Years, another of Lynd Ward's novels in woodcuts. All of the above became collectors' items. In all we published 12 books between 1931 and 1937, and four poetry pamphlets, two of them by Conrad Aiken and William Faulkner. We sold them ourselves to bookstores during our lunch hours, and the Olddens did the billing and bookkeeping.

As if life weren't full enough, we joined with a small group to start a private press of our own. While working with Lynd Ward on his novels in woodcuts, I came to know him and his wife, May McNeer, a writer of books for children. When Lynd proposed that with other friends we start a cooperative press to make and publish fine books, doing as much of the work as possible by hand, I welcomed the prospect. Equinox Cooperative Press combined a variety of talents: Lynd and John Heins were artists, Henry Hart (then at Scribner's) was our editor, Mildred and Stanley Oldden were business people who liked books, Belle Rosenbaum was assistant editor of the Herald Tribune Books, Tony and I were designers, and most important, Lew White was an excellent printer who had a shop where we amateurs were allowed to set type by hand. We met at night, after our day's work, to set type, airbrush covers, fold sheets, and sew signatures. Our first book was Now that the Gods are Dead written especially for us by Llewelyn Powys; it was followed by Nocturnes, three stories by Thomas Mann, who signed many copies for us; Three Blue Suits, stories by Aline Bernstein, Thomas Wolfe's intimate friend; Prelude to a Million Years, another of Lynd Ward's novels in woodcuts. All of the above became collectors' items. In all we published 12 books between 1931 and 1937, and four poetry pamphlets, two of them by Conrad Aiken and William Faulkner. We sold them ourselves to bookstores during our lunch hours, and the Olddens did the billing and bookkeeping.

One of our last books was a trade book, Ferdinand Lundberg's Imperial Hearst which we took on with fear and trembling, wanting to take a swat at Hearst, and knowing that we could easily be squashed by him. But Hearst never bothered us, the book was well-reviewed and received and was sold eventually to the Modern Library. Some of the material in the book was used by Orson Welles and Herman Mankiewicz in the making of the film Citizen Kane, and the author of Imperial Hearst was able to get some retribution in the courts. [6]

The time came when all of the members of Equinox had added responsibilities to the point where we could no longer set type at night or sell books at noon. We closed shop with money in the bank and all the members friends.

At Harrison Smith and Robert Haas some very good books were published during the mid-thirties. One was Isak Dinesen's Seven Gothic Tales. I was one of the first to read the manuscript, which came in through Dorothy Canfield Fisher, and immediately I felt its powerful originality and came under its spell. Other good titles were Andre Malraux's Man's Fate and the Babar books for children. But the firm was not flourishing. In 1936 Harrison Smith and Robert P. Haas merged with Random House. Louise Bonino and I again went along, she to continue the development of a department for children's books, and I to be in charge of design and production. Random House was then a small firm which published, on one hand, the Modern Library series, and on the other, imported sheets from the Nonesuch Press and undertook a few books with Elmer Adler. One of the trade books I planned which gave me especial satisfaction was Gertrude Stein's The Geographical History of America, of which she wrote to Bennett Cerf, "I must say I liked enormously the printing of it. It's about the best printing I have ever seen of a purely commercial book."

After our marriage there was no longer a dire need for me to earn money. I left Random House early in 1937 for the birth of William Glick.

When he was followed by Thomas I became impatient with sitting in Carl Schurz Park beside a perambulator and we moved to Connecticut. After the move I did some free-lance designing for publishers, but found that from a distance I could not insist on the faithful following of my layouts as a manuscript moved through its manufacturing phases.

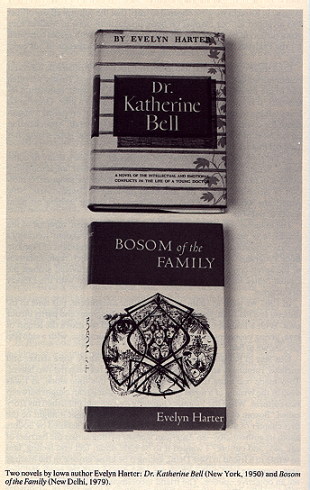

During the years when our sons were young I wrote a little chapbook, Printers as Men of the World, for an organization called the Typophiles. Following that I undertook a novel, Dr. Katherine Bell, about a youtg woman studying medicine at Iowa in the days when there was considerable hostility toward women among students and professors. When she came to practice she herself took a conservative view about medical care. All this was in contrast to the liberalism of her lawyer husband. I sent this to the agent, Diarmuid Russell (son of A. E.), who sold it to Doubleday, and it was published in 1950. It was well-received, notably by Lewis Gannett in the daily Herald Tribune.

Tony came home one night in the summer of 1957 to say that he had been queried by the Ford Foundation about whether we would be interested in going to India for six months to work with local publishers and printers on the improvement of the appearance of their books and their economical production. We had never thought of going to India, knew very little about the country, but the idea appealed to us as a fine adventure, particularly since we could work as a team. Our sons were in college and Tony was able to get a leave of absence from Viking.

The Ford Foundation had sent James Laughlin of New Directions to India to lay the groundwork for a trial project for helping publishers there. He with others had set up the Southern Languages Book Trust in the four southernmost Indian states -- Madras (now Tamil Nadu), Kerala, Mysore (now Karnataka), and Andhra Pradesh. There was an American adviser, Arthur Isenberg, but all the directors of the Trust and the staff were Indian. Although the publishers, printers, artists, and booksellers produced books in their local languages (Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, and Telugu), they could also speak English well enough that communication was possible. In fact sometimes English was the only language by which they could talk to each other. We were dubbed consultants, as were others who had preceded us, dealing with costing, promotion, and sales.

We were based in Madras on the Bay of Bengal, a city laid along a wide beach where fishermen mended their nets before sailing out in their catamarans. Madras, although a very big city, still had some rural charm; along with modern buildings there were buffalo wallows and little enclaves of people living in palm leaf huts. We could encounter festival parades on the street, see saris in brilliant colors washed and spread on the river banks. There were concerts by musicians using instruments we'd never heard before, sarod and veena and shahnai.

We suffered the initial shock of seeing poverty, disease, and death at close hand. We went through a period of discomfort before accepting the fact that we were here to do what we could in our own way. We visited printing plants, gave talks at professional meetings. Sometimes our "lectures" (and we were often dubbed "Dr." no matter how much we tried to discourage this) were preceded by a little ceremony of invoking a god. A priest would break a coconut, place it on a silver tray where camphor burned, lift it to the god with a prayer, and hand it to an acolyte who would offer the tray to those present that each might partake of the blessed coconut. Sometimes we performed in halls where General Cornwallis (posted to Madras after Yorktown) and other former British officials in their red uniforms looked back from the walls at us.

We were treated with the greatest courtesy. We had to make speeches because they expected it, even though we didn't always understand their English or they ours. What we found most useful was to ask them to bring their books and place them on a long table. Around this we could sit and discuss alternate ways of handling certain features. They were very hesitant about differing with someone who was older than they, or to disagree in public with a woman. Sometimes Tony and I purposely argued with each other on a point to show that it was possible. They enjoyed that.

One handicap they suffered was a lack of good papers and we could do nothing but commiserate. What paper was available was rationed. It was discouraging to talk about good composition and presswork when the type would have to be printed on stock often flimsy, or as uneven and rough as blotting paper. In spite of this a certain amount of excellent printing was done on imported paper, particularly colorful wall calendars and posters. I can report that good Indian-made paper is somewhat more available to printers now than it was in 1957.

We made trips out of Madras to other important cities: to Bangalore, where the Maharajah of Mysore (who was also the governor of the state) presided in his brilliant red and gold costume. In Hyderabad we set up an exhibit of the best Indian books we had found. Two Indians and I put on a brief demonstration of the steps a manuscript goes through in production. In Trivandrum our "function" was on the grounds of a college where, at the entrance, several beautiful young girls swung censers of incense on us as we entered and bade us dip our fingers in a liquid which no doubt had been blessed. At this city occurred the only incident of the trip which indicated that we were not welcome. This was no more than some invited guests not coming to a dinner. Kerala is a state of contradictions: it has a strong Communist party; it is the most Christian, most highly educated, and most densely populated of all the Indian states. It has tremendous unemployment, and yet has a successful cooperative publishing house and a bookstore which pays good royalties directly to authors.

While in Madras Tony and I wrote a manual based on Indian conditions entitled A Book Production Planning Guide. This was done with the help of a few printers we had met who could acquaint us with local customs.

We were packing to leave Madras to head for home. Tissue paper and many presents, all heavy, lay on every chair and friends waited to take us to the airport. A young publisher with whom we had worked turned up asking if we could see him alone. It was necessary to do so, and we took him out on the hotel balcony which overlooked the bay. The young man said, "Before you go, Mr. Glick, I would like to have your blessing as my guru." Tony looked blank. His pipe was in his mouth and he had no idea how to give a blessing as a guru, but he managed to say, "Inasmuch as it is in my power, 1 do give my blessing." The young man later started the first book club in South India.

To me as a writer the trip meant that I now had material of endless interest to me, layers on layers: on the meetings, confrontations, disappointments, satisfactions between Indians and Americans. The relationships, comedies and tragedies in the British experience had been well-covered from Rudyard Kipling to E. M. Forster and others, but little had been done by American writers. Over the next ten years 1 wrote a number of stories on this subject, most of which were printed in American quarterlies. Many of them were listed in Martha Foley's annual anthology and one -- "The Stone Lovers" -- was reprinted in Prize Stories of 1971, the O. Henry Awards. [7]

My stories have dealt with such subjects as two Indian families trying to agree an the amount of a dowry; of an Indian young man who cannot bear his inability to return the hospitality of his American friends; an American family suffering culture shock on their return to New York after a year in India; an American missionary back in the U.S. remembering an abandoned temple with stone lovers which she and her husband thought of as symbols of their love.

In 1961, four years after the Ford Foundation trip, we went to South Asia on a longer mission, this time sponsored by the American Institute of Graphic Arts and financed by the specialists program of the state department. This covered ten months, starting in Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia, continuing on through Burma, East Pakistan (as it was then), India, West Pakistan, Ceylon (very briefly), Iran, and Turkey.

The staff in Washington who were preparing our schedule queried the Asian countries to know whether they wanted us. The only countries on our list who did not welcome the idea were Indonesia and Ghana (although later, after Sukarno was gone, Indonesia invited us). We prepared an exhibit to go with us as accompanying baggage; it was planned to show both good and bad features of American bookmaking. Also we were to invite Asian publishers who were already doing good work to send samples to New York for a judged exhibition to be mounted on our return by the American Institute of Graphic Arts.

When we came down at Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia for the first meeting of our trip, the flags were out. Not for us, but for the delegates to the Colombo Plan conference, whose hall we used after they were through. Fortunately for us, Malaysia had adopted the Roman alphabet as a means of holding its three language groups together-the Chinese, the Indians, and the Malays. Through arrangement with the United States Information Service our visit was sponsored by an organization called Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, established to forward Malay as the national language. The energetic head of this, Tuan Syed Nasir, saw to it that we visited Penang in the north and Johor Bahru in the south (from which we went across the causeway to Singapore). We gave seven talks in Malaysia, one to a Rotary Club, conducted four seminars, set up our 44 exhibition panels six times for schools, ran films on paper making, photoengraving, offset lithography, and showed slides of four advertising designers -- Rand, Lionni, Lubalin, and Dorfsman. We visited private printing plants on different levels -- from a new offset plant with air-conditioned camera room and press room and a Monophoto machine, all the way down to miserable little shops crowded and lit by only one light bulb hanging from the ceiling. This was to be the pace through the coming months in 16 cities in seven countries.

In Burma one night it was so hot we decided to project our film on the making of a photoengraving on a whitewashed compound wall. As I watched people arrive I saw nursing mothers and women with small children taking the front benches. And they stayed, eyes fixed on the screen all through the unbearable suspense of etching and routing and tacking the metal on the block, to the climax when the first proof rolls off the press to victorious music on the tape.

We arrived in Bombay, India, on the very day of what the astrologers said was a bad conjunction of planets. Many shops were closed as people crouched in their houses awaiting the end of the world. The American cultural affairs officer feared that we wouldn't have an audience, but about 25 brave men came and returned to their homes quite safely.

We had to schedule West Pakistan and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) separately, as they were a thousand miles apart and spoke different languages. In Karachi we were cheered to learn that the cultural affairs officer had arranged for our manual on book production, done in Madras four years earlier, to be edited and printed for Pakistanis with prices corrected for the Pakistan rupee. They had distributed it in anticipation of our coming.

In all these countries that had formerly been under British rule we could communicate in English, but when we reached Iran and Turkey we often had to ask for interpreters. This was a handicap, for when translation intervenes, it is hard to say anything casual, or to make a joke. Once when I was talking to some librarians in Ankara I said that in preparing a manuscript for composition you must have a passion for detail. Apprehension on the faces of the audience told me that something had gone wrong, but I did not inquire more closely.

By the time we had been away for ten months we were ready to come home. When we arrived in New York we found that an astonishing number of examples of good printing had come in for the proposed exhibition of Asian printing at the American Institute of Graphic Arts. Now Americans would realize that Asians were no longer writing on palm leaves or papyrus.

The material was judged by Professor Alvin Eisenman, director of the graphic arts program at Yale; August Heckscher, President Kennedy's special consultant on the arts; and Datus C. Smith, president of Franklin Book Programs. After an opening in New York at which representatives of the seven countries were present, the exhibition traveled around the United States for two years and was eventually lodged with the Library of Congress.

In 1967 we went to south Asia on another assignment, this time to Indonesia and Pakistan, partly for Franklin Book Programs and partly on our own. With a Franklin representative at the wheel we drove the length of Java, giving programs at Jakarta, Bandung, and Surabaya, with a side trip on our own to Bali.

Our stay in Pakistan was not very satisfactory; there were strikes and curfews, rumblings and anxieties about relations between the two halves. Tony made one more trip to Pakistan in 1970, this time alone, as I was deep in the writing of a novel about an Indian young man caught between two cultures. When the Virginia Quarterly Review had published my story called "Bosom of the Family," readers had suggested that it might be the first chapter of a novel. After the book was done I was assailed by doubts about its authenticity-an American woman writing across the barriers of age, sex, and culture? I wanted it to be right about fact and feeling, and so wrote to a friend in New Delhi, asking if he knew anyone in the Madras area, someone who didn't know me, who would read the book and give me an objective opinion. The friend recommended Kasturi Rangan, who had been for years the chief Indian correspondent for the New York Times and was also editor of Katzaiyazi, a literary magazine in the Tamil language. To my astonishment Mr. Rangan said that he found only trifling errors and that he liked the story so much that he wanted to serialize it in his Tamil magazine and would arrange to have it done in English in the Journal of the Indian Housewife, this to protect copyright. He also took it to the publishing house of Arnold Heinemann (India) who published it in book form in English, hardbound for use in libraries. [8]

I am sometimes asked what I think we accomplished on our sorties into Asia. I can answer only that we rarely knew when seeds fell on fertile ground. It was a Johnny Appleseed enterprise. I am inclined to think that our influence was strongest when we made personal friends in those countries. Over the years there has been a procession of Asians through our house in Connecticut; letters and some visitors come even now when my husband is gone.

If our little literary group could gather in ectoplasm around the table at Youde's boardinghouse, what would we say about the necessity of choosing between the work and the life? We would have behind us some good work, though probably not as much or as good as we had hoped. Marquis Childs has published seven books, of which Sweden, the Middle Way is best known. Ruth Lechlitner has continued to write and publish poetry all her life. Paul Corey published four novels set in Iowa farm country; Lee Weber placed poems in Harriet Monroe's Poetry, a Magazine of Verse; Charlton Laird wrote two novels and more than 20 works on language and pedagogy; Douglas Branch published four books relating to the American frontier; and I was the author of two novels and 24 short stories. The very talented Buel (Griffith) Beems contributed a dozen fine stories to national periodicals before leaving New York to return to Cedar Rapids to devote his life to a family business. Wendell Johnson wrote three books of which Because I Stutter was one of the earliest on this speech difficulty. [9]

If our little literary group could gather in ectoplasm around the table at Youde's boardinghouse, what would we say about the necessity of choosing between the work and the life? We would have behind us some good work, though probably not as much or as good as we had hoped. Marquis Childs has published seven books, of which Sweden, the Middle Way is best known. Ruth Lechlitner has continued to write and publish poetry all her life. Paul Corey published four novels set in Iowa farm country; Lee Weber placed poems in Harriet Monroe's Poetry, a Magazine of Verse; Charlton Laird wrote two novels and more than 20 works on language and pedagogy; Douglas Branch published four books relating to the American frontier; and I was the author of two novels and 24 short stories. The very talented Buel (Griffith) Beems contributed a dozen fine stories to national periodicals before leaving New York to return to Cedar Rapids to devote his life to a family business. Wendell Johnson wrote three books of which Because I Stutter was one of the earliest on this speech difficulty. [9]

Charles Brown Nelson would have done fine work if he had lived longer. One of our classmates, although she never contributed to the Iowa Literary Magazine, was Mildred (Augustine) Wirt Benson, who must be Iowa's most prolific author; she wrote dozens of books for children, in one year turning out 13 full-length volumes under five different names. [10]

Some member of our literary group hypothetically gathered around the table might point out that two American authors, at least, combined glorious writing with lifelong labor in the workaday world: William Carlos Williams spent 40 years as a practicing doctor while producing memorable poems and prose, and Wallace Stevens wrote poetry of the highest reach while serving as an active vice-president of a Hartford insurance company. In Remembering Wallace, recollections by Stevens's friends, one of them said, "He thinks it is silly that a man's ability to live in both worlds should be so widely doubted." And another said, "It is not a choice between excluding things."

Literary valuations change over the years, and the only judge of the quality of a private life must be in the person who experienced it. Our Iowa writers would probably say that yes, livelihood is necessary, but that it is their delight to drag a small bit of meaning (as Rebecca West has put it) across the threshold of consciousness into recognition.

NOTES:

[1] Some of these students were the same who are named and discussed in Charlton Laird's "The Literati at Iowa in the Twenties," Books at Iowa 37 (November 1982): 16-37.

[2] See Sargent Bush, Jr., "The Achievement of John T. Frederick," Books at Iowa 14 (April 1971): 8-23, 27-30.

[3] Ansley had left the Iowa post to become editor of Columbia University Press. There he conceived the idea of a one-volume encyclopedia, and himself carried through as editor. My life was tangential to the encyclopedia years later when my husband, Milton B. Glick, proposed to the Viking Press (where he was in charge of design and production) the publication of a desk encyclopedia to be based on the Columbia lectern volume. As a result he made 16 detailed cost estimates on the desk volume and worked on its production over several years.

[4] See Evelyn Harter, The Making of William Faulkner's Books, 1929-1937: An Interview with Evelyn Harter Glick (Columbia: Southern Studies Program, University of South Carolina, 1979).

[5] Courtesy of the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, New York Public Library.

[6] Henry Hart wrote the whole story of Equinox Cooperative Press in A Relevant Memoir (New York: Three Mountains Press, 1977).

[7] Among short stories by Evelyn Harter are "The Stone Lovers," Southwest Review (Winter 1970): 41-50; "In My Next Incarnation," North American Review (November 1965): 32-36; "A Kingly Exit," Prairie Schooner (Fall 1966): 250-260; "Greet You with Garlands," Southwest Review (Autumn 1968): 349-358; "The Landlady," Southwest Review (Winter 1975): 15-24; "Next Summer in Bangkok," Virginia Quarterly Review (Winter 1978): 137-147; and "Till All Can Enter Paradise," Texas Quarterly (Winter I 975): 57-69.

[8] Bosom of the Family is to be published in the United States in March 1985 by St. Martin's Press/Richard Marek.

[9] Names of other writers who were published may be found in Charlton Laird's aforementioned article, "The Literati at Iowa in the Twenties."

[10] See Mildred Wirt Benson, "The Ghost of Ladora," Books at Iowa 19 (November 1973): 24.