To: UI Special Collections

William T. Rigby and the Red Oak Boys in Louisiana

TERRENCE J. WINSCHEL

From Books at Iowa 63 (November 1995)

Copyright: The University of Iowa

The winds of war which swept across the Louisiana bayous and fueled the flames of secession in the winter of 1860-61 also rushed over the endless plains and ignited pas sions of patriotism in the people of eastern Iowa. The farmers of Iowa depended on free navigation of the Mississippi River to transfer the bounty of their harvest to world markets. Upon the secession of the Southern states, and in particular Louisiana and Mississippi, the great river was closed to navigation, which threatened to strangle the economic interests of the Hawkeye state. The people of Iowa looked to preservation of the Federal government as the surest method of maintaining their vital economic interests and rallied around the flag in this time of crisis.

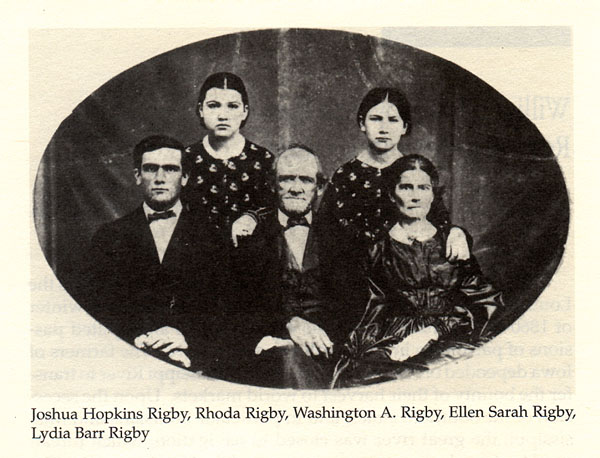

The national crisis enveloped the family of Washington Augustus Rigby. Born in Knox County, Ohio, on October 2,1814, Washington Rigby lost his father when only four years of age. The burden thus placed on his widowed mother of raising seven children was too great for her to bear and, at the age of eleven, Washington went to live with an uncle in Licking County, Ohio. At fourteen, the young boy set out on his own and moved first to Belleville in Richland County where he worked in the fields and developed a love of farming. At eighteen, he taught school but after two years of teaching grew restless and turned his eyes to the virgin soils of Iowa. Ever an adventuresome man, Washington migrated across the Mississippi River to Bloomington (now Muscatine), Iowa, where he met and married Lydia Barr. [1]

Married on May 19,1837, the Rigbys set up house in a log cabin that Washington built at Red Oak Grove on the banks of Rock Creek, northwest of Tipton, the seat of government for Cedar County. The Rigbys were a perfect match. Washington is described as being "tall, muscular, very strong, with curly hair and sparkling blue eyes." Trained by his mother to be "upright, kind, dependable and resourceful," he found Lydia to be a "perfect helpmate." A woman considered by many as "courageous, industrious, instinctively well-bred she was the finest type of pioneer woman." These noble characteristics were the foundation on which they would raise a family. [2]

Married on May 19,1837, the Rigbys set up house in a log cabin that Washington built at Red Oak Grove on the banks of Rock Creek, northwest of Tipton, the seat of government for Cedar County. The Rigbys were a perfect match. Washington is described as being "tall, muscular, very strong, with curly hair and sparkling blue eyes." Trained by his mother to be "upright, kind, dependable and resourceful," he found Lydia to be a "perfect helpmate." A woman considered by many as "courageous, industrious, instinctively well-bred she was the finest type of pioneer woman." These noble characteristics were the foundation on which they would raise a family. [2]

Their first child was born on November 3, 1840, and named William Titus in honor of Washington's father. Another son, Joshua Hopkins, was born in 1844, followed by two daughters, Rhoda in 1848 and Ellen Sarah in 1850. Although each had a special place in their father's heart, it was William who became his father's confidant, advisor, and friend.

The log cabin in which they lived had become much too small for the Rigby family, so Washington built a larger one nearby. Will and Joshua slept in the loft and often the boys would awake on a cold winter's morning to find themselves covered with snow which had sifted through the cracks. By 1854, however, Washington had become a prosperous farmer through industry and thrift and built a fine two-story wood home with a porch on the front from which he could look out over the seemingly endless plain.

Accustomed to "hard work and hearty play," the Rigbys enjoyed life, yet Washington watched with mounting anxiety as the sectional crisis threatened to tear the nation asunder. A devout Methodist who believed that the blessings of liberty should be enjoyed by all of God's creatures, he was active in the Underground Railroad. He even purchased a closed carriage, the first in the neighborhood, to conceal the human cargo he assisted to freedom. Opposed to the war on religious grounds, he prayed earnestly that the great conflict would not engulf his family, but fate would dictate otherwise. [3]

With the firing on Ft. Sumter in April 1861, followed by the call for troops from President Abraham Lincoln, war fever gripped Iowa and men flocked to the colors. Will wrote to his sister Rhoda who was then at school in nearby Mt. Vernon: "The only thing we talk of now is the war news from the South. Perhaps you would like to know what we are doing to put down the Traitors. Our county has raised one company & is raising another. We intend to equip them ourselves. At a meeting held in Tipton on Wednesday last $1200 was raised for that purpose." Although anxious to enlist, he sadly informed her, "Father gave them $20 instead of letting me go. I guess that is more than I am worth so the company does not lose any thing." [4]

Thousands of troops were raised in Iowa and sent to the armies in the field. Iowans served in the Union armies that fought at Wilson's Creek, Pea Ridge, Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Corinth, and elsewhere and played a significant role in the operations that centered on the Mississippi River valley. But Union reverses, most notable of which were in the East, resulted in horrifying casualty lists, weakened Northern resolve, and led the war to continue longer than most people had anticipated. In the summer of 1862, Lincoln issued a call for 300,000 additional men to fill the vacant ranks. It was a call that William Rigby had to answer.

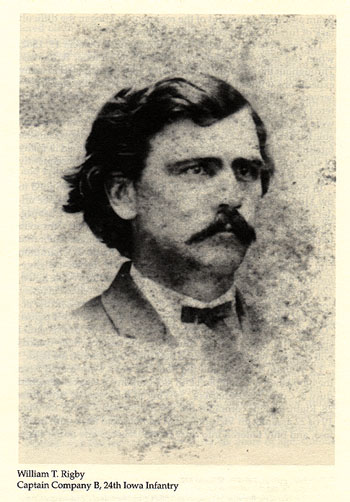

On the farm in Red Oak Township, William pleaded with his father for permission to enlist and finally, in July, gained his consent. As with all things throughout his life, Rigby entered into service with conviction and a strong faith in God, and his actions were governed by those pioneer qualities of courage, industry, and self-reliance. He assisted in enrolling the 102 volunteers who would comprise Co. B, 24th Iowa Infantry, including his cousins Alfred, Jesse, and Martin Rigby. Known to all the men from Red Oak Grove as an honest, fair, and decent man, Rigby was meticulous and commanded the respect of those he knew. He was elected second lieutenant on July 22 -- an honor of which he was immensely proud. [5]

On the farm in Red Oak Township, William pleaded with his father for permission to enlist and finally, in July, gained his consent. As with all things throughout his life, Rigby entered into service with conviction and a strong faith in God, and his actions were governed by those pioneer qualities of courage, industry, and self-reliance. He assisted in enrolling the 102 volunteers who would comprise Co. B, 24th Iowa Infantry, including his cousins Alfred, Jesse, and Martin Rigby. Known to all the men from Red Oak Grove as an honest, fair, and decent man, Rigby was meticulous and commanded the respect of those he knew. He was elected second lieutenant on July 22 -- an honor of which he was immensely proud. [5]

In addition to the Red Oak boys, the company consisted of men from Tipton, Mechanicsville, Rochester, and Clarence, all small towns in Cedar County, and a scattering of men from the adjacent counties of Johnson, Linn, and Muscatine. Once filled, the company was ordered by Governor Samuel Kirkwood into quarters at "Camp Strong" in Muscatine, on the Mississippi River, where they were mustered into Federal service on August 29,1862. The company was commanded by twenty-two-year-old Capt. Stephen W. Rathbun with Benjamin F. Fobes, both from Tipton, serving as first lieutenant. By September 18, the regiment was fully formed and consisted of ten companies with an aggregate of 979 men. To a man, the unit pledged to abstain from drinking liquor during their term of service and became known as the Iowa Temperance Regiment. Eber C. Byam, a native of Canada residing in Mt. Vernon, was elected colonel. At thirty-six years of age, Colonel Byam assumed command of the regiment and began the difficult task of turning raw recruits into soldiers. [6]

The regiment remained at Camp Strong until October 19,1862, when the men were sent by transport to Helena, Arkansas. Throughout the fall and winter months, they participated in many expeditions without seeing action. The regimental historian observed: "While no considerable body of the enemy was encountered upon any of these expeditions, and no practical results were accomplished by them, the troops suffered almost unendurable hardships from exposure to storms of rain and snow, and the fatalities which resulted were as great as those sustained in many of the hard-fought battles in which the regiment subsequently participated." [7]

In the spring of 1863, however, the 24th Iowa was assigned to the XIII Corps and ordered to join the Army of the Tennessee under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant then operating against Vicksburg. The regiment saw only limited action on May 1 at Port Gibson in which its casualties were one killed and five wounded. Their first test in combat came two weeks later in the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16. In the largest, bloodiest, most decisive engagement of the Vicksburg campaign, the Iowans lost thirty-five killed, 120 wounded, and thirty-four missing. Brig. Gen. Alvin P Hovey, commander of the Twelfth Division, XIII Corps, praised the actions of Colonel Byam and his regiment as he wrote in his report: "Of the ... Twenty-fourth Iowa, in what words of praise shall I speak? Not more than six months in the service, their records will compare with the oldest and best tried regiments in the field." [8]

Lt. William T. Rigby and the Red Oak boys were spared from the bloodshed at Champion Hill as Company B was on detached duty at Corps Headquarters. Serving in this capacity until June 28, Rigby and his comrades did not participate in either the May 19 or 22 assaults on Vicksburg that were hurled back with heavy loss, and only entered into duty in the trenches late in the siege. Following the surrender of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, the regiment marched on Jackson and participated in the short-lived siege of Mississippi's capital city, then returned to Vicksburg for some much-needed rest.

The intense heat of Mississippi and the hard campaigning of the spring and summer took a heavy toll on the Iowans and several men were discharged for disability. Colonel Byam also resigned from the service on June 30 and Lt. Col. John Q. Wilds of Mt. Vernon assumed command of the regiment. In Company B, Captain Fobes fell victim to illness and died on August 5. Command of the company devolved to Lieutenant Rigby who wrote of Fobes, "The Regt. has lost in him one of its best, if not its best officer, & the community where he lived has lost a man, who had he lived would have certainly distinguished himself." [9]

At 6 a.m. on Sunday, August 2, the regiment left Vicksburg on the steamer Diana and arrived at Natchez at 5 o'clock that afternoon. On August 6, while still in Natchez, Rigby was promoted captain, at which rank he served for the remainder of the war. Five days later, on Tuesday, August 11, the regiment boarded the transport Des Arc and, along with the 56th Ohio and 1st Missouri Battery, left Natchez at 10 a.m. The men moved downriver to Port Hudson, Louisiana, then to Carrollton, near New Orleans, where they arrived at 10 p.m. the following night. [10]

At 6 a.m. on Sunday, August 2, the regiment left Vicksburg on the steamer Diana and arrived at Natchez at 5 o'clock that afternoon. On August 6, while still in Natchez, Rigby was promoted captain, at which rank he served for the remainder of the war. Five days later, on Tuesday, August 11, the regiment boarded the transport Des Arc and, along with the 56th Ohio and 1st Missouri Battery, left Natchez at 10 a.m. The men moved downriver to Port Hudson, Louisiana, then to Carrollton, near New Orleans, where they arrived at 10 p.m. the following night. [10]

Anxious to explore the Crescent City, Rigby went into New Orleans on company business and recorded in his diary on August 17, that he "saw everything of interest." The captain may also have noticed during his visit to the South's largest city military activity which signified the start of an expedition. On September 5, Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin left New Orleans with 4,000 men of the XIX Corps on a movement to capture Sabine Pass. [11]

A rather large man with dark hair and beard, Franklin was an 1843 graduate of West Point and stood first in a class of thirty-

nine cadets. An engineer by training and experience, he served with questionable distinction in the early days of the war at Bull Run, on the Peninsula, and during the Maryland campaign. Given command of the "Left Grand Division" in Ambrose Burnside's Army of the Potomac, his troops were dealt a severe blow at Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. The Federal debacle at Fredericksburg proved Franklin's undoing, and Burnside demanded his removal from the army. Rather than be dismissed from the service, however, he was ushered out West and given command of the XIX Corps. [12]

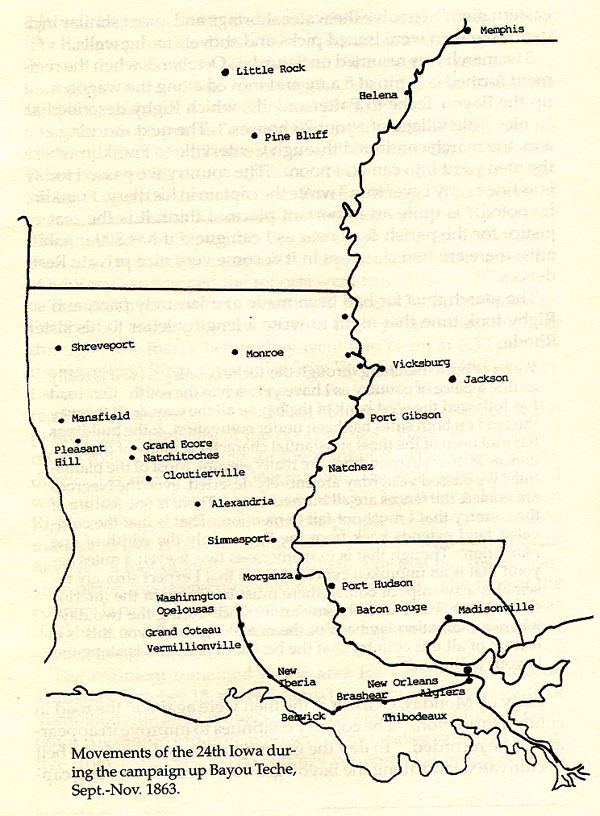

On September 8,1863, two gunboats were lost in action against the fort at Sabine Pass and the operation was abandoned. Returning to New Orleans, Franklin next attempted to reach the Texas stronghold by an overland route. Reinforced by elements of the XIII Corps, including the 24th Iowa recently arrived from Vicksburg, Franklin's command took up the line of march. Lieutenant Colonel Wilds and the men of the former Iowa Temperance Regiment (a month in New Orleans will corrupt anyone) crossed the Mississippi River on Sunday, September 13, to Algiers. There the regiment boarded cars of the Opelousas & Great Western Railroad for the journey to Brashear City which was reached the following day. Rigby recorded in his diary that "It is the most forsaken looking place I ever saw," and added, "I hope our stay in it will be brief. " [13]

It was. Late that day, the regiment crossed Berwick Bay to Berwick City and camped a half mile back of the town which Rigby described as nothing more than a "cluster of houses." The camp was poorly situated and water was scarce presenting a serious concern to the soldiers. On Tuesday, September 15, Rigby noted in his diary: "Some of my boys crossed the Bay in the forenoon to get water which is very scarce on this side. As they were coming back they were fired upon by a foolish Sentinel on this [side] who happened to belong to the 19th Corps. The affair served to increase the bad feeling already existing between our men & the eastern men." To solve the water shortage and avoid similar incidents, the men were issued picks and shovels to dig wells. [14]

The march was resumed on Saturday, October 3, when the regiment formed column at 8 a.m. and moved along the wagon road up the Bayou Teche to Pattersonville, which Rigby described as "a nice little village of about 20 houses." The next morning at 6 a.m. the march continued through Centerville to Franklin where the men went into camp at noon. "The country we passed today is as fine as any I ever saw," wrote the captain in his diary. Franklin, he noted, "is quite an important place. I think it is the seat of justice for the parish & as near as I can guess it has 500 inhabitants, there are two churches in it & some very nice private Residences." [15]

The march thus far had been made at a leisurely pace, and so Rigby took time that night to write a lengthy letter to his sister Rhoda:

We have been marching through the Teche country ... & it is really as fine a piece of country as I have yet seen in the south. Our road has followed the west bank of the Bayou all the way. & all the way the land on both sides has been under cultivation, & the buildings have all been of the most substantial character & many of the Residences & their surroundings are really elegant. Most of the plantations we passed yesterday are entirely deserted, even the Negroes are gone & the fences are all burned up.... There is one feature of the country that I must not fail to mention. That is that the cultivated land extends back from the Bayou only the width of one plantation. Though that is in many cases two & even 3 miles beyond that is an unbroken cypress woods that I expect strongly resembles a swamp. of course there must be Farms in the interior some where, but I scarcely saw an instance during the two days where a plantation lay back of the one along the Bayou this is a feature of all this country that the best & dryest land is along the Bayous & Rivers. [16]

Early on Monday, October 5, the men were again on the road in column formation. "The country continues to improve in appearance," he recorded. "To day the ground has been dryer & the belt of cultivated land along the Bayou grows wider." The young captain was impressed with the beauty of the land and the following day he entered in his diary: "We have passed to day a great deal of land that has never been broken. The country reminds me strongly of some of our Iowa Prairies, the difference is that the land here is almost a perfectly level plain." [17]

As the troops pushed deeper into the interior of Louisiana on Wednesday, October 7, news was read that Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans and his Army of the Cumberland had gained a "great victory" over Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg. The report, of course, was false as Rosecrans had been driven from the field at Chickamauga on September 20. Although the men knew better than to accept such rumors as fact, they raised a hearty cheer for "Old Rosy" and hoped the reports were true. [18]

The march resumed at a more rapid pace at 7 a.m. on Saturday, October 10, and the Iowans covered twenty-four miles, pushing through New Iberia, before they went into camp at 6:30 p.m. on the Vermillion River, three miles from Vermillionville (present day Lafayette). "The country we passed over is a fine rolling prairie," reads the diary entry for that day, "but it is thinly settled & the [white] inhabitants are of the poorest class. Water is very scarce on the road & we suffered for the want of it. The roads are very dusty. It is one of the hardest marches the Regt. ever made & I was quite tired when we went into camp." In a letter to his father, Rigby expressed sympathy for the people he saw: "How they manage to live is past my comprehension as a great part of them have not a foot of land under cultivation or that has the appearance of having been cultivated for a long time. The face of the country is naturally handsome, it is a gently rolling prairie & was delightful to me in spite of its desolate appearance, it reminded me so strongly of home."' [19]

The regiment remained in the area for several days and on Thursday, October 15, moved camp to within a half mile south of Vermillionville and bivouacked on the plantation of former Governor Alexandre Mouton, who served as Louisiana's chief executive from 1843-1846. "The country we passed through is much the same as on the march from New Iberia," noted Captain Rigby, "most of it seems to have been at some time under cultivation but now the greater part of it is entirely open & grown up with grass. The houses along the Road are only cabins & are generally inhabited by the poorest kind of whites & [a] large proportion, probably a majority of them can scarcely understand a word of English. They are French & Creoles, & speak the French language & have learned it to their Negroes." [20]

In a letter to his brother Joshua written on October 23, Will confided his frustrations with the leadership of William B. Franklin and Union leadership in general:

It is hard to see that our commander has any definite object to accomplish by this expedition. It is now said that the expedition to Texas has been abandoned & that we are to go from Opelousas to Alexandria on Red River. I will be sorry if this proves true, for now that we have gone this far I would like to see a little of Texas. But I will think as I did when we started from New Orleans that a great mistake was made in sending us here instead of to Tenn to reinforce Rosecrans. Indeed I wonder that we were not sent to him directly from Vicksburg. If Rosecrans had been heavily reinforced from Grant's army during the months of July & August, I think affairs there would now be in a much better condition & as for the Rebels on this side of the Miss [River] they are perfectly harmless even if we let them alone entirely. [21]

On Thursday, October 22, the regiment left camp at 6:30 a.m. and late that afternoon bivouacked at Grand Coteau. Rigby boasted in his diary that "The boys have marched splendidly today." The following day the men marched through a heavy rain and reached Opelousas where they rested for several days. [22]

Resuming the march on Sunday, November 1, the Hawkeyes reached Carrion Crow Bayou and went into camp. "Charlie Williams of Company K died soon after we got into camp," recorded Rigby. The next day, another member of the regiment, Jeremiah C. Gue from Tipton, captain of Company C, was killed by guerrillas while in command of a foraging party in search of sweet potatoes. [23]

Increased enemy activity was ominous and on Tuesday, November 3, Rigby's twenty-third birthday, Brig. Gen. Stephen G. Burbridge's command was attacked by a body of Confederates near Carrion Crow Bayou. "The enemy in overwhelming numbers were pressing me," reported Burbridge. Although outnumbered, Burbridge's men fought with grim determination until Union reinforcements arrived and checked the enemy's attack. In what is referred to as the Battle of Bayou Borbeaux, Burbridge's division lost 680 men. The 24th Iowa, however, was not engaged and the entire Federal force commenced to withdraw to Vermillionville. [24]

While camped at Vermillionville on Monday, November 9, Will penned a lengthy letter to his sisters Rhoda and Ellen in which he wrote:

There is no doubt but there is a large force of the enemy near us, but they do not seem inclined to give us battle. For the past three days the Regt. has been called into line about Five in the morning to stand under arms until near sunrise. We have an order to continue this until further orders. It is to guard against a surprise by the enemy as just at daybreak is the time usually chosen for such an attack. If the enemy chooses to come he will find us waiting for him. [25]

Two days later he wrote to his father from camp at Vermillionville, a letter in which he discussed the quality and quantity of rations the men received. "The beef that we draw is of the Best quality, we get it right off the Prairie & it is fat & tender. The supply seems to be inexhaustible, besides supplying ourselves, we have since we started on this campaign sent large numbers of cattle to New Orleans, yet we have no difficulty in getting all that we require." [26]

On Monday, November 16, the Federal withdrawal resumed as the men retired an additional thirteen miles and went into camp at Lake Tasse, near New Iberia. Two days later, unbeknownst to Will, tragedy struck the Rigby family as Rhoda died of what the doctor called "inflammation of the bowels" -- appendicitis. Although both Joshua and his father wrote letters informing Rigby of her death, the letters never reached him. It was not until a month later that he learned of Rhoda's death. [27]

Sunday, November 29, found the regiment still camped at New Iberia, from where Rigby complained in a letter to his younger brother: "It seems to me that Gen. Franklin is more jealous of the safety of the citizens around here, three fourths of whom are open Rebels, than of the comfort of his troops. I heartily wish we had some other man to command us." In December the weather turned cold and was, he wrote, "for this latitude very cold. Ice was formed in small vessels one fourth of an inch in thickness. The ground was also frozen & in the shade did not thaw out during the day." In words of admiration he related to Joshua:

Our men really suffered for several days from the cold. It makes me indignant to go through the company & see how they are provided for. Yet the cheerfulness with which the boys bear their privations is heroic. We have been more than seven months without tents of any kind & are now in pressing need of clothing & blankets. Yet the men bear it all patiently that too when we are idle in camp & there is no possible excuse for withholding supplies from us.

In writing to his father concerning the suffering of his men due to exposure, the captain lashed out, "Gen. Franklin is to blame for this suffering .... The gen. knows or ought to know that we are without tents & destitute of clothing & there is no possible excuse for keeping us without them." [28]

On Monday, December 7, permission was finally granted by Franklin for the men to secure boards with which to make winter quarters. Company B of the 24th Iowa went out with teams to get the necessary amount. Rigby recorded in a letter to Joshua:

We crossed the Bayou [Teche] & went out 8 mi before we got what we wanted. We passed plenty of plantations where there was plenty of boards, but the owners had protection papers & we had to go on until we found a man without them. At last we found one & we went at his property in a way that made him very indignant. We tore down his cotton gin & took as much of his fencing as was necessary to load the wagons & left him in rather a bad humor. [29]

While in camp at New Iberia, Lieutenant Colonel Wilds, Capt. Jacob Casebeer of Company D from Iowa City, and one sergeant from each company were sent home on recruiting duty. Although Rigby longed to see home, he was content to remain in camp and relished the letters he received from his family. On December 5, however, Will received a letter from his sister Rhoda along with news of her death. In a letter to his father, the grief-stricken soldier wrote:

[cousin] Martin had a short letter from Sister Melissa telling him that my sister Rhoda was dead. I had just finished reading a letter from her when Martin handed me his letter. It is very sad news to me yet I will not say a word that will add to the grief of those at home. I feel that I am better able to bear my burden than are you. My poor Mother how will she bear the loss I pray that God may give her strength equal to the burden he has laid on her. ... Do not I pray you let the thought of my loss add to your grief but let me rather assist you in bearing yours.

In closing he wrote, "I must dash my cup of joy to the ground." [30] The regiment left New Iberia on December 19 and marched fifty-four miles in three days to Berwick City. On December 25, the men boarded a train and rode to Algiers where the Iowans spent the holidays. Although the weather was cold and rainy, Rigby got a room in a private house with Capt. Edwin H. Pound of Company C in which they filled out their paperwork during the day and slept on the floor at night. [31]

On New Year's Eve, Rigby and Pound crossed the river to New Orleans. The young captain described how he spent the holidays in a letter to his father:

Friday was a gay day in the city it was full of officers & soldiers all of them bent on making the most of their holiday & I fell in with the crowd enough to have a good time myself. We stopped at a good lodging house where we had a nice room & a clean bed, luxuries that I have not enjoyed for a long time & it seemed quite novel to me this little taste of citizen life after so much campaigning. Thursday night I went to the circus & Friday night to theatre. I know that you will not blame me when you remember how long I have been away from amusements of any kind. The performances at both places were good & in good taste, but I was more interested in the audience than by the play, it seemed so novel to be in a crowd of well dressed Ladies & gentlemen after being away from such occasions for nearly two years. [32]

He was later chided by Josh for attending the theatre: "Under your circumstances there is perhaps no harm and little danger in going to the theater, but I think as I said before that it has very bad associations, the lowest of women, the vilest of men, and it is not a healthful moral atmosphere for one to remain in long." Joshua, who became a Methodist minister, was shocked to learn from his brother of the Temperance Regiment's activities during the holidays for Will wrote:

The boys had managed to get some liquor during the evening & quite a number of them got onto a regular spree. It was Christmas night & I let the Boys have their own way & they made a good deal of music. One of them John Pitman [of Tipton] talked very abusively about me at any other time I would not have stood it a moment but considering that it was Christmas night & a good many of the Boys were on a spree I thought I would let him have his say if it gave him any satisfaction. I am more than ever disgusted with drunkenness & there is no denying that there is too much of it in the army & that it is on the increase. When we are on a campaign the men can not get it, but when we are near the city a great many of them will have it & some will get drunk, My Boys have spent a big pile of money since we were paid off. It is an unfortunate thing for our pockets that we came to the city & got our pay just at the beginning of Holiday week & a fortunate thing for the tradesmen of the city quite a number of them will have the whole of their two months pay behind them & if it were twice as much they would do the same. They have all been over to New Orleans once or twice & of all the places in the world to spend money in, it is the best. [33]

On Sunday, January 17,1864, the division was ordered to duty in the New Orleans defenses. Later that week, the regiment moved across the Mississippi River from Algiers and took the train from New Orleans to the shore of Lake Pontchartrain, then steamer and schooner across the lake to Madisonville, Louisiana, near the mouth of the Tchefuncta River. [34]

From Madisonville, Rigby wrote to his father on Friday, February 19:

It is not easy to find news enough here to fill a letter. It is with us as every where there is a lull in active operations. I fully believe that it is the calm that precedes a storm, but it is a question if the storm will reach us. I think the coming campaign will be as active as any the war has yet seen. The rebel leaders have no thought of submission & they still have the men & material to make a vigorous resistance to our advance. Still I hope that the coming campaign will be the last of the war. It can be made so if our rulers but properly employ the forces which the people is placing at its disposal. To end the war we have only to crush the two great armies of the rebellion, the one under Lee & the one opposed to Grant & surely we are strong enough to do that in one campaign, let the rebel chiefs be ever so skillful. But the rebellion is not going to collapse from merely letting it alone & if this work that I spoke of is not done by the first of October I think the war will drag its tedious length through another winter & at the least I think we will have to spend another winter in the service as the gov. can not muster its soldiers out of service as soon as the fighting is over. We are throwing up very strong works around this place as strong as any I ever saw. I judge from this that it is to be made a depot of some importance though at present I can not see for what purpose it is needed. [35]

Work on the fortifications at Madisonville continued until the end of the month when, as Rigby predicted, active operations began. Returning to New Orleans via the Pontchartrain Railroad, the captain complained: "I think that piece of Railroad between Lakeport & the city is worse than anything else of the kind in the U.S. The locomotives on it are old fashioned asthmatic things. The cars are not over 12 ft long are with out brakes starting & stopping is effected by a succession of jerks that is apt to upset one if he is not on his guard." [36]

In a letter to his brother written from Algiers on Saturday, February 27,1864, he speculated as to the future:

What is before us now I can not tell but the prevailing opinion is that we are going up the Teche again. I hope it may prove incorrect. I have no desire to see that country again. l would much prefer going to Texas. Gen. McClernand assumed command of the corps on the 23d issuing a congratulatory address to his troops which you will see in the papers. I am glad of the change. I am not in love with McClernand but I prefer him to Ord he has more energy, a strong desire to hurt the rebels. One thing is certain if there is to be any active campaigning in this department we are elected for our full share of it. [37]

On March 3, the regiment left Algiers by train en route to Brashear, which they reached at sundown, and were sent across the bay to Berwick City. "I think we will start on Monday or Tues day of next week & then comes marching again. I am glad of it," he informed his brother, stating "it agrees with me better than anything else." His prediction, however, was premature as ten days later the regiment was still encamped at Berwick City. In a letter to josh, Will described the preparations his men made for the upcoming march:

Yesterday we turned over our tents only retaining one wedge tent to the company for the use of its officers. There are but two wall tents in the Regt. one for the Major & one for the Quartermaster & Adjutant. All our unnecessary baggage was packed in boxes & today started for New Orleans where it will be stored until called for. We start out much better provided for than when we left last fall the boys all have a wool blanket & most of them have a Rubber [ground cloth] with them. They all carry their knapsacks this time & have a change of clothes with them. We have not drawn shelter tents yet but will get them at Franklin when the men will be well equipped for a campaign. I have everything with me that I will need my trunk, my Desk with all the Company Books & papers & all my blankets.... We had orders to start this morning at 7 but for some reason it was changed to 7 tomorrow morning which happens to be Sunday again. Then we will be off & the orders we received 3 days ago said that we were to prepare for a long & rapid march. I think we will not be disappointed of it. [38]

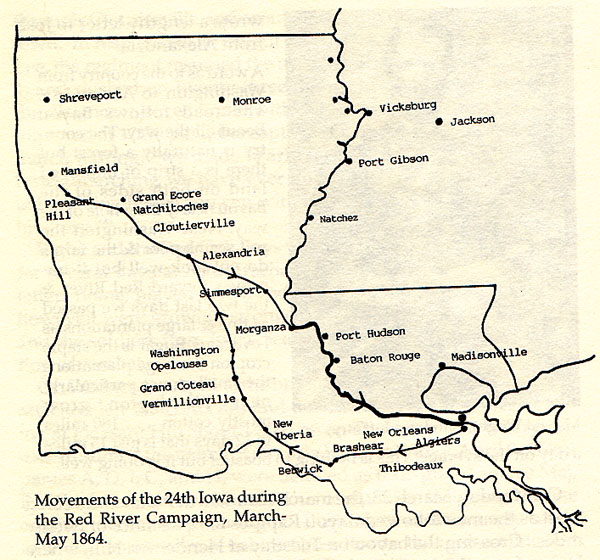

The campaign began on Sunday, March 13, 1864, as the regiment left Berwick City and marched up Bayou Teche. Pushing over the same route as the previous fall, the Iowans marched through Franklin, New Iberia, Opelousas, and arrived within seven miles of Alexandria on March 25. The following day, Will wrote a lengthy letter to Josh from Alexandria:

A word as to the country from Washington to Alexandria. The road follows Bayou Beouf all the way. The country is naturally a forest but there is a strip of improved land on both sides of the Bayou nearly the whole of the way. Near Washington the soil seems poor & the farms do not look well but it improves toward Red River & the two last days we passed as fine & large plantations as I ever saw. Sugar is the staple crop on the large plantations the smaller ones particularly near Washington grow mostly cotton.... 180 miles in 12 days that is just 15 miles a day on the average. This is nothing to boast of but it is doing well.[39]

last days we passed as fine & large plantations as I ever saw. Sugar is the staple crop on the large plantations the smaller ones particularly near Washington grow mostly cotton.... 180 miles in 12 days that is just 15 miles a day on the average. This is nothing to boast of but it is doing well.[39]

On Monday, March 28, the march resumed at 7 a.m. and veered west as the men followed Bayou Rapides for a distance of twenty miles. Crossing the bayou on Tuesday at Henderson Hill, where Union forces had captured the 2nd Louisiana Cavalry and four guns of Edgar's Texas Artillery on March 21, the Iowans camped on Cane River at Monett's Ferry, having marched fourteen miles. Rigby recorded that the column moved "slowly & halted so often that it tired me more than the march the day before it was after 4 o'clock when we went into camp." A detail from the regiment was sent to help bridge the river which was completed by noon the following day. [40]

Screened by a strong cavalry force under the command of Brig. Gen. Albert Lee, the regiment started at 6 a.m. on Thursday, March 31. Crossing the stream on a pontoon bridge, the rugged soldiers from Iowa followed the course of Cane River for sixteen miles through Cloutierville and went into camp one mile beyond the town. In response to an urgent request for support from General Lee, the regiment resumed the march at 5:30 a.m. on Friday, April 1, and pushed on twenty-three miles to Natchitoches, covering the distance in seven hours with only four halts for rests. Reaching town at 12:30 p.m., the captain of Company B boasted of the march writing, "we made nearly four miles an hour. That is the fastest marching we have ever done & when you hear any one tell of doing better you can with good reason doubt the truth of his story." [41]

Rigby and the Red Oak Boys welcomed the opportunity to rest for several days at Natchitoches, during which time they wrote letters home, played cards, and bathed in the river. Indications, however, were growing stronger that battle was soon imminent and the soldiers from Iowa cleaned their equipment in anticipation of combat.

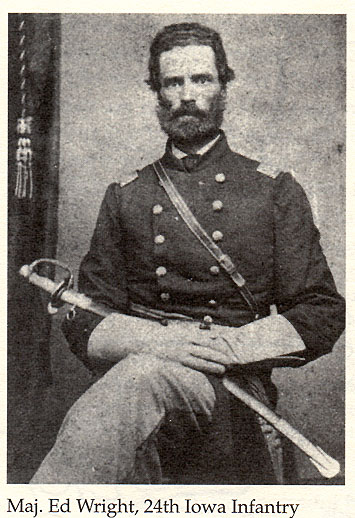

On Wednesday April 6, the brigade to which the 24th Iowa was attached left Natchitoches and marched thirty-five miles, arriving at Pleasant Hill about 1:30 p.m. on Thursday. The weary soldiers resumed the march at an early hour on Friday, April 8. Companies A, D, I, C, and H, were detailed as train guard and so Maj. Ed Wright marched with only four companies, including the one commanded by Captain Rigby. Pushing over the muddy roads to within seven miles of Sabine Cross Roads, the men established camp on a branch of St. Patrick's Bayou. The soldiers immediately set about gathering firewood and cooking rations when suddenly, battle erupted near Mansfield, ten miles to the northwest. [42]

On Wednesday April 6, the brigade to which the 24th Iowa was attached left Natchitoches and marched thirty-five miles, arriving at Pleasant Hill about 1:30 p.m. on Thursday. The weary soldiers resumed the march at an early hour on Friday, April 8. Companies A, D, I, C, and H, were detailed as train guard and so Maj. Ed Wright marched with only four companies, including the one commanded by Captain Rigby. Pushing over the muddy roads to within seven miles of Sabine Cross Roads, the men established camp on a branch of St. Patrick's Bayou. The soldiers immediately set about gathering firewood and cooking rations when suddenly, battle erupted near Mansfield, ten miles to the northwest. [42]

At 2 p.m., the sound of artillery was heard indicating that the head of the column was heavily engaged. Instinctively, Rigby and his men knew their services would soon be required and prepared to advance to the aid of their comrades. Ordered forward at 3 o'clock, the Hawkeyes moved at the double-quick for nearly six miles before they arrived at the scene of action and deployed into line of battle. As the Red Oak Boys arrived at the front, they "found the road so full of teams and stragglers on foot and on horseback as to make it impossible to move any farther." Swinging his men from column into line of battle, Major Wright was ordered to hold his men in reserve behind the crossroads as the unit numbered only six officers and 182 men. [43]

Federal troops had been driven from their first position on Honeycut Hill and, with the arrival of these fresh troops, formed a second position one mile to the rear at-Sabine Cross Roads. The brigade commander reported: "Under a heavy fire the men lay for over an hour, not daring to advance against an enemy who numbered thousands to our hundreds, and until their ammunition was almost entirely expended, while the enemy, plainly in sight, was adding to his force and extending his line, which from the first greatly outflanked us." In response to the rapidly deteriorating situation, the 24th Iowa was ordered into position on the left of the line. One officer recorded that the men "were soon exposed to the fire of the enemy's battery, which poured shrapnel and shell upon us." The troops could not stand long in such an exposed position and, Major Wright reported, "were compelled to retire before a much superior force both on our left flank and in our front." [44]

All along the front, Union forces, hard pressed and low on ammunition, were forced from the field. The retreat soon turned to rout. In the gathering darkness soldiers in blue panicked on the narrow, crowded road. Many of the Federals threw down their weapons and accouterments in a desperate effort to elude Confederate pursuers. The retreat continued throughout the night to Pleasant Hill, a distance of eighteen miles, where the Iowans finally went into camp at 7 a.m. on April 9. Although exhausted, a roll call was taken which revealed the extent of their loss. The 24th Iowa lost 18 percent of their number as thirty-five men were killed, wounded, or missing. Among those captured by the enemy were Surgeon John M. Witherwax of Davenport, Assistant Surgeon Henry M. Lyons of Cedar Rapids, and, in Company B, Rigby's cousin Jesse was listed as missing. [45]

The fight near Mansfield had been a disastrous affair for the Union army under Nathaniel Banks which lost almost 3,000 men, twenty cannon, and 250 wagons. Although only a portion of his available force had been engaged, Banks was badly shaken. When his army was attacked at Pleasant Hill late on the afternoon of April 9, his confidence was shattered. Banks abandoned the campaign and ordered the troops back to Alexandria. From Pleasant Hill, the army moved by forced marches through Grand Ecore and Natchitoches to Cloutierville, during which time the 24th Iowa saw minor action at the crossing of Cane River on April 22-23, and stumbled into Alexandria on April 26. "It is enough to say that the march was one of the hardest we ever made," Will informed his brother josh, "as we were kept up the greater part of 4 nights in succession & when we could catch a little sleep we had nothing to cover us but a rubber blanket." [46]

The army remained at Alexandria until May 13, as the Red River was unseasonably low and the Union fleet was stranded above the falls. To make matters worse, the enemy established a blockade below the city in an effort to cut the Federal supply line. In response to the critical situation, Union engineers constructed dams in hopes of creating a pool of water sufficient in depth to float the boats over the rapids. Thus, Banks had to delay farther retreat in order to enable the engineers to finish their work and protect the fleet.

"The rebel blockade on Red River was so well maintained" lamented Rigby, "that we were quite shut out from the rest of the world while we lay at Alexandria. After one large mail going out had been captured Gen. Banks would allow no more to go out & soon after this the river was closed to us entirely not until after at least 3 transports & two of the Musketo Boats (Signal and Covington) had been captured & burned by the enemy." Life in the beleaguered city soon became unpleasant as the Union soldiers lived on reduced rations and under threat of an attack. The captain recalled, "At Alexandria we were continually expecting an attack from the enemy & Gen. Banks kept our corps oscillating backwards & forwards between Alexandria and Middle Bayou 7 m. from town." Skirmishing occasionally flared and the Iowans had a sharp encounter with the enemy at Graham's Plantation on May 5. "The last week of our stay there," recorded Rigby, "we were camped on this Bayou to keep the enemy at a comfortable distance while preparations were made for the retreat." [47]

Many anxious days passed, not only for the army at Alexandria, but for the families in Iowa who longed to hear from their soldiers. By May 13 the fleet was over the rapids and the retreat was resumed as Union soldiers took up the line of march at 3 p.m. and headed southeast toward Simmesport on the Atchafalaya River. When they reached the area below Alexandria where the enemy had blockaded the river, the men were surprised to find the captured mail strewn along the riverbank. Rigby related in a letter to his brother:

The bank of the river was covered with letters they [the Confederates] had opened & read. Some of the boys found letters they had themselves written at Alexandria. I warrant you the Rebs had a jolly time reading them & that they found some not flattering opinions expressed of Gen. Banks. The worst of it is we had received pay & some of the boys sent their money by mail & it is probably lost. [48]

Captain Rigby and the Red Oak Boys took the road through Marksville to Simmesport, which they reached on the 17th. The commander of Company B was pleased to note that the march was completed "without any thing of special interest occurring except that on the 16th [at Mansura] the Rebels made a strong show of giving us battle on an open prairie several miles in width but seeing our strength they finally respectfully declined." [49]

The Rigbys were greatly relieved when a letter finally arrived from Will in which he explained the reason for not writing sooner and detailed the withdrawal from Alexandria to Simmesport. From camp near Morganza, he penned a letter to Joshua which began:

A very long time has elapsed since I last wrote to you. I am sure you will think either that I had forgotten you or that I had been unwell but neither supposition is correct. I have been well & have thought of you every day in the week probably every hour in the day. [50]

In tracing the course of his company's service, the captain wrote that the army remained in Simmesport on May 18 and 19, during which time the regiment changed camp several times-evidence of the confusion which permeated army headquarters. The Atchafalaya is a broad stream, noted. Rigby of the river at Simmesport, "it was bridged by placing transports side by side in the stream & lying the bridge across the ... [bows] on this the entire army with its wagons crossed." The 24th Iowa crossed on the afternoon of May 20, and by sundown the army was over the bridge which was then broken up and the boats steamed down river. The march resumed at 10 o'clock that night and the Iowans started for the mouth of Red River which they reached at 9 o'clock next morning. The following day, unable to secure river transports, the soldiers again took up the line of march to Morganza, on the Mississippi River, which was reached before noon on May 22. [51]

"So ends our Red River expedition," wrote a frustrated Captain Rigby. "I think that a more laborious or fatiguing one has not been made by any of our forces & it is disheartening after all the hard ships we had undergone to think that the expedition to say the least is a failure." Although pained by a sense of failure, the young officer was relieved to notify his family that, "The boys are all well though they are all badly worn down. Hard marching, loss of sleep & insufficient rations will wear down the strongest constitution & all these we experienced. For two weeks we have been on 2/3 rations of hard tack & coffee with occasionally a slice of fat meat." He admitted, "For the first time I am the worse of campaigning. I feel worn & am completely stalled [constipated] (that is not a nice word but you will understand it), on the Hard tack & coffee." [52]

To further relieve the anxiety of those at home in Cedar County whose sons were in the company, he informed his family that "We have good news from Jesse [Rigby, who had been captured at Mansfield on April 8]. He is a live & well & at Tyler Texas [Camp Ford prison]. Martin [Rigby] got a letter from him a few days ago that was brought through under a flag of truce. [Benjamin F.] Jenkins [from Clarence] is also there so that all our boys are accounted for but [James R.] Collins. Poor fellow, I am afraid we will never hear mote of him." Collins died of disease at Mansfield on April 8, 1864. [53]

Exhausted by the labors of the campaign, his thoughts turned to more pleasant times at home in the company of his family. "I would like of all things," he expressed to Joshua, "to sit down to a good meal at home tonight & drink a cup of Mother's tea & this is about the first time I have expressed such a wish." With such pleasant thoughts to warm his soul, the weary captain closed his letter and sought the comfort of a good night's sleep-his first in many weeks. [54]

The regiment remained at Morganza for two weeks during which time the men took part in an expedition to the Atchafalaya River. In a sharp skirmish with the enemy near Rosedale Bayou on May 30, Capt. Benjamin G. Paul of Company K, from Wyoming, Jones County, was killed and four enlisted men woundedthe action proved to be their last in Louisiana. [55]

On June 6 the Hawkeyes took a steamer to Kinnerville (present day Kenner), near New Orleans. Following three weeks of rest, the regiment boarded the steamer Crescent which carried the men down river to Algiers on June 26. After disembarkation, the rugged soldiers from Iowa boarded a train and rode the cars west to Thibodaux. In a letter written from Thibodaux on July 1, 1864, Rigby confessed to his younger brother, "I am getting tired of this kind of life. Any kind of service is preferable to it. For my part I prefer to campaign all the time & am restless when we are in camp." [56]

While the regiment was stationed at Thibodaux, John C. Starr of Company B from Tipton died on July 1 of "congestion of the brain." His death was the last suffered by the regiment during its service in Louisiana. Three days later, on July 4, the troops celebrated Independence Day with speeches, singing, and music, and a sword was presented to Colonel Wilds by the noncommissioned officers and privates that cost $200. Captain Rigby was pleased by the presentation and noted in a letter to his brother: "I am glad the Regt. has made the present. The Col. has been very faithful ever since he has been with us & whatever his faults he has been uniformly kind & considerate to his men. I am sure he will prize the gift as highly as any one could." [57]

While the regiment was stationed at Thibodaux, John C. Starr of Company B from Tipton died on July 1 of "congestion of the brain." His death was the last suffered by the regiment during its service in Louisiana. Three days later, on July 4, the troops celebrated Independence Day with speeches, singing, and music, and a sword was presented to Colonel Wilds by the noncommissioned officers and privates that cost $200. Captain Rigby was pleased by the presentation and noted in a letter to his brother: "I am glad the Regt. has made the present. The Col. has been very faithful ever since he has been with us & whatever his faults he has been uniformly kind & considerate to his men. I am sure he will prize the gift as highly as any one could." [57]

By mid-summer, active operations in Louisiana had come to a close while, in Virginia, Union forces were knocking at the gates of Richmond and Petersburg. Rumors began to circulate among the troops that they would soon be sent to Virginia and reunited with their former commander, U.S. Grant. Rigby, however, knew better than to trust camp talk. "It is not very wise to speculate upon army movements," he wrote, "but I am of the opinion that some active campaigning is just ahead of us." The astute captain observed:

Our Div. seems to be entirely broken up & it is said that our Brigade is to be put in the 19 Corps. A large part of that corps is in camp here waiting for ocean transports to move them to the new theater of operations but as yet we can only conjecture where that is to be. Whatever their destination ours is to be the same so that our stay here will be brief. [58]

Orders arrived on July 7 for the regiment to return to Algiers, which fueled speculation as to their destination. The Iowans took up the line of march and, as they left Thibodaux behind, few of the men had any regrets. They reached the railroad after a march of only five miles and quickly entrained for Algiers. Before leaving Thibodaux, Rigby scribbled a few lines to his brother in which he commented: "Whatever is before us I can say that I am ready for it. I never yet shrunk from active work nor do I feel like doing so now but the idea has been strong with me to day that we are to see warm work again soon." [59]

By July 21, after weeks of tense waiting at Algiers, Rigby notified those at home that "it has been settled definitely that we are to go to the east.... It is understood that Baltimore is our destination but of course that will depend much upon the turn affairs take during the next week." Although he realized that bloody work lay ahead, the young captain was anxious to leave Louisiana and was pleased by the prospects of an ocean voyage. "At any rate we are bidding goodbye to this Dept.," he wrote, and upon reflection added, "I am glad of it." [60] On July 22, 1864, the Regiment did indeed leave for the Eastern Theatre.

The service of the 24th Iowa in Louisiana had come to an end. It can be summed as a period of activity without purpose. The twelve months spent in Louisiana reflected the political and military situation that existed within the department: poor, often inept leadership on the part of both Franklin and Banks, lack of a clear military objective, the meddling of politics in military operations, and the use of the military in carrying out purely political objectives. Perhaps more convincing than any argument, the absence of purpose reveals Federal perception as to the reduced significance of Louisiana and the Trans-Mississippi Department following the capture of Vicksburg and Port Hudson.

Lest this detract from the soldiers who served in Louisiana, it must be said that their courage, endurance, and devotion to duty were seldom equaled, never excelled. Captain Rigby and the Red Oak boys had faithfully performed their duty, often under trying circumstances and had demonstrated the finest qualities of veteran soldiers. Their record of service was one of which they could proudly boast for, as one veteran claimed for the regiment, "Everywhere, in camp or garrison, upon the march, in battle, and under all vicissitudes of its long and arduous service, it maintained in the highest degree the honor of the flag and its State." The regimental historian wrote in similar praise: "The archives of the State of Iowa and of the War Department at Washington contain no more glorious record of valor and patriotic service than that of the Twenty-fourth Iowa Infantry Volunteers." [61]

NOTES

[1] Alice Rigby, The Rigby Family, (Published privately for family consumption, 1990) p 5. Washington Augustus Rigby died on March 22, 1881, his wife Lydia Barr Rigby died in 1896, both are interred in Red Oak Cemetery near Stanwood, Iowa.

[2] Ibid., pp. 5-6.

[3] Ibid., p. 6.

[4] Letter, William T. Rigby (hereafter cited as WTR) to Rhoda, April 1861. (Unless stated otherwise, all letters cited are in the William T. Rigby Papers, MsC 82, Special Collections Department, University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa.)

[5] Roster and Record of Iowa Soldiers in the War of the Rebellion, 6 vols. (Des Moines: Emory E. English, 1908-1911), Volume 3, p. 872. (Source hereafter cited as Roster & Record.) Both Martin and Jesse were sons of WTR's uncle Caleb Pumphrey Rigby who resided in Fremont Township, Cedar County, near the village of Mechanicsville. Martin was wounded at Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864. He died in 1918 and is buried in Mt. Vernon, Iowa. Jesse was taken prisoner at Mansfield on April 8,1864. Following the war he became a minister and moved to Oregon.

[6] Ibid., pp. 781, 795, 797, 825, and 872.

[7] Ibid., p. 782.

[8] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 128 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), Series 1, Volume 24, Part 1, p. 583; O.R. 1,24,2, p.44. (Source hereafter cited as O.R. followed by series number, volume, and part.)

[9] Letter, WTR to brother, August 18, 1863. Capt. Benjamin Fobes is interred in Section O, Grave 4283, Vicksburg National Cemetery, Vicksburg, Mississippi.

[10] Diary of William T. Rigby, entries for August 2-12,1863, William T. Rigby Papers, MsC 82, Special Collections Department, University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa. (Source hereafter cited as Diary WTR, date of entry.)

[11] Ibid., August 17,1863; Mark Mayo Boatner, The Civil War Dictionary (New York: David McKay,1959), p. 716.

[12] Ezra J. Warner, Generals in Blue (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964), pp. 159-160.

[13] Diary, WTR, September 13-14,1863.

[14] Letter, WTR to Rhoda, October 4, 1863; Diary WTR, September 15-16,1863.

[15] Letter, WTR to Rhoda, October 4,1863; Diary, WTR, October 4,1863.

[16] Letter, WTR to Rhoda, October 4, 1863.

[17] Diary, WTR, October 5-6,1863.

[18] Ibid., October 7, 1863.

[19] Ibid., October 10,1863; Letter, WTR to father, October 12,1863.

[17] Diary, WTR, October 15, 1863; Letter, WTR to brother, October 22, 1863; Letter, WTR to brother, October 23,1863.

[18] Ibid., October 7, 1863.

[19] Ibid., October 10. 1863; Letter, WTR to father, October 12, 1863.

[20] Diary, WTR, October 15, 1863; Letter, WTR to brother, October 22, 1863; Letter WTR to brother, October 23, 1863

[21] Letter, WTR to brother, October 23, 1863.

[22] Diary WTR, October 22-23,1863.

[23] Ibid., November 1-2,1863. Charlie Williams was from Wyoming, Jones County. Capt. Jeremiah C. Gue is interred in Section R, Grave 16607, Vicksburg National Cemetery Vicksburg, Mississippi.

[24] Ibid., November 3,1863; O.R. 1/26/1 pp. 360-361.

[25] Letter, WTR to sisters, November 9, 1863.

[26] Letter, WTR to father, November 11, 1863.

[27] Diary, WTR, November 16,1863; Letter, Father to WTR, November 29,1863. Washington Rigby's letter to his son did not arrive in camp until after Will was informed by cousin Martin Rigby that Rhoda had died. In the absence of Lt. Col. John Wilds, Maj. Ed Wright of Springdale, Cedar County, assumed command of the regiment. Wright was promoted colonel on November 18, 1864, following the death of Wilds, and on March 13, 1865, was made brevet brigadier general of volunteers.

[28] Letter, WTR to brother November 29,1863; Letter, WTR to brother December 1863; Letter, WTR to father December 4, 1863.

[29] Letter, WTR to brother December 1863.

[30] Letter, WTR to father December 5, 1863.

[31] Letter, WTR to father January 3, 1863.

[32] Ibid

[33] Letter Joshua H. Rigby to WTR undated, letter in private collection; Letter WTR to brother January 4, 1864.

[34] Letter, WTR to father January 24, 1864.

[35] Letter, WTR to father February 19, 1864.

[36] Letter, WTR to brother February 27,1864.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Letter, WTR to brother March 8,1864; Letter, WTR to brother March 12, 1864.

[39] Letter, WTR to father March 16,1864; Letter, WTR to brother March 26, 1864.

[40]Letter, WTR to father April 2, 1864.

[41] Ibid.

[42] O.R. 1,34,1 pp 285 and 287.

[43] Ibid., pp. 273, 285, and 287.

[44] Ibid., pp. 285-288.

[45] Ibid., pp. 259 and 286; Roster & Record, Volume 3, p. 872.

[46] Boatner, The Civil War Dictionary, pp. 715-716; Letter, WTR to brother May 23,1864.

[47] Letter, WTR to brother May 23, 1864.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Roster & Record, Volume 3, p. 788

[56] Letter;WTR to brother July 1, 1864.

[57] Ibid.; Roster & Record, Volume 3, p. 879; Letter, WTR to brother July 7,1864. Wilds was promoted colonel on June 8, 1864. He was seriously wounded in the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, on October 19, 1864, and died in a Winchester hospital on November 18.

[58] Letter, WTR to brother July 17, 1864.

[59] Ibid.

[ 60] Letter, WTR to brother July 20,1864. (Although the letter was dated on July 20, he did not finish writing it until July 21, 1864.)

[61] Roster & Record, Volume 3, p. 794.

-END-