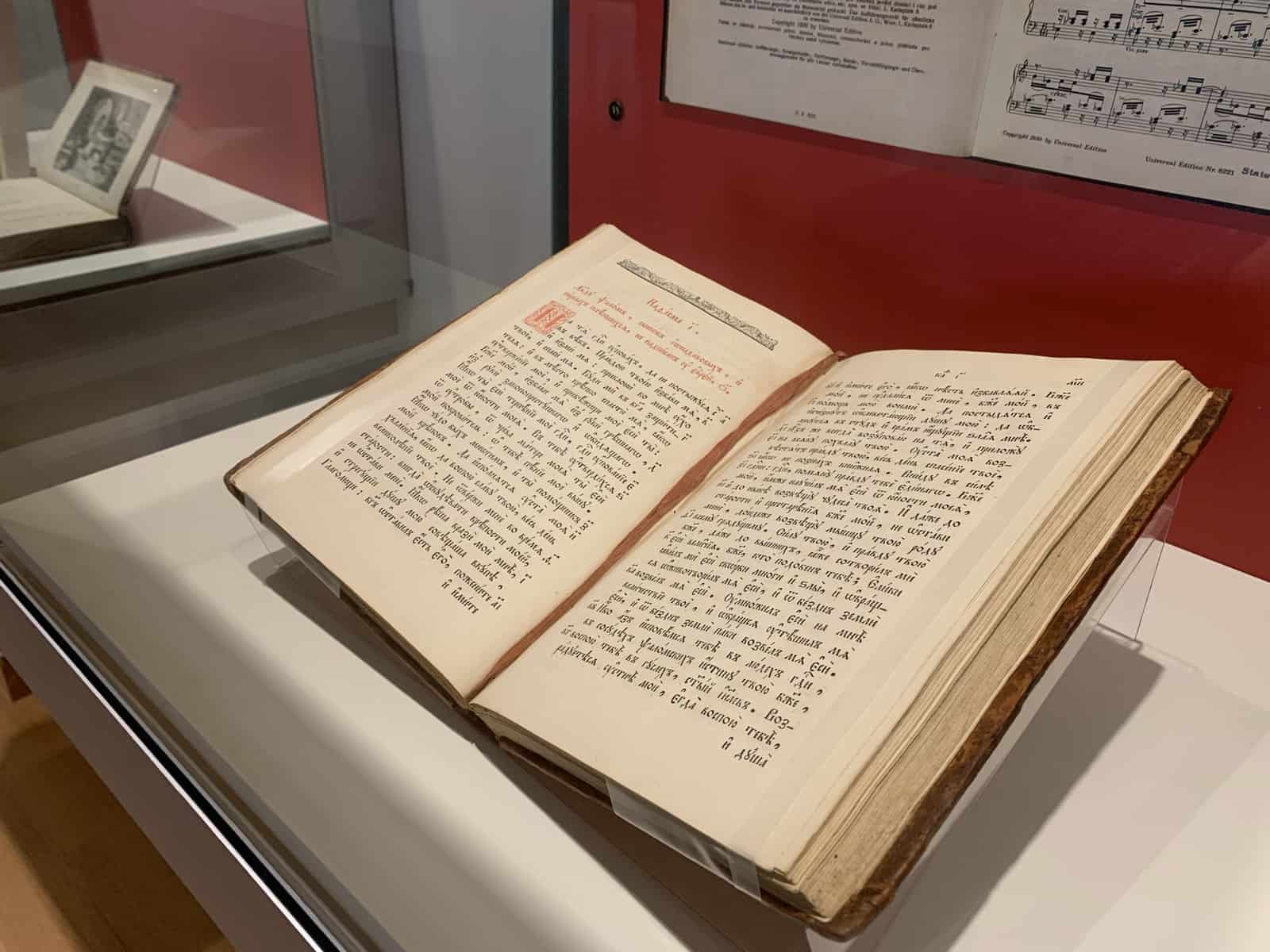

P︠S︡altirʹ. (Bible. Psalms.) Moskva: Synodalbhaia Tyts, 1851. Russian. [x-Collection, BS1425 C4 1851] University of Iowa Special Collections & Archives.

The 1851 Russian P︠S︡altirʹ (psalter) is an interesting book, as it is emblematic of the changing society in which it existed. The book is printed in kirillitsa, which is a traditional Russian script that mimics the earliest Russian writing and Church Slavonic of much earlier writings. Even in the middle of the nineteenth century, the book would have looked like a relic. By this time, Peter the Great had introduced a much plainer, simple font known as the Civic Type that could be found in many books and documents. Imperial Russia was a quickly changing place; there existed scientific writings printed in Civic Type alongside Psalters like this one printed in archaizing letters.

-Dr. Eric Ensley, Curator of Rare Books & Maps, University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections & Archives

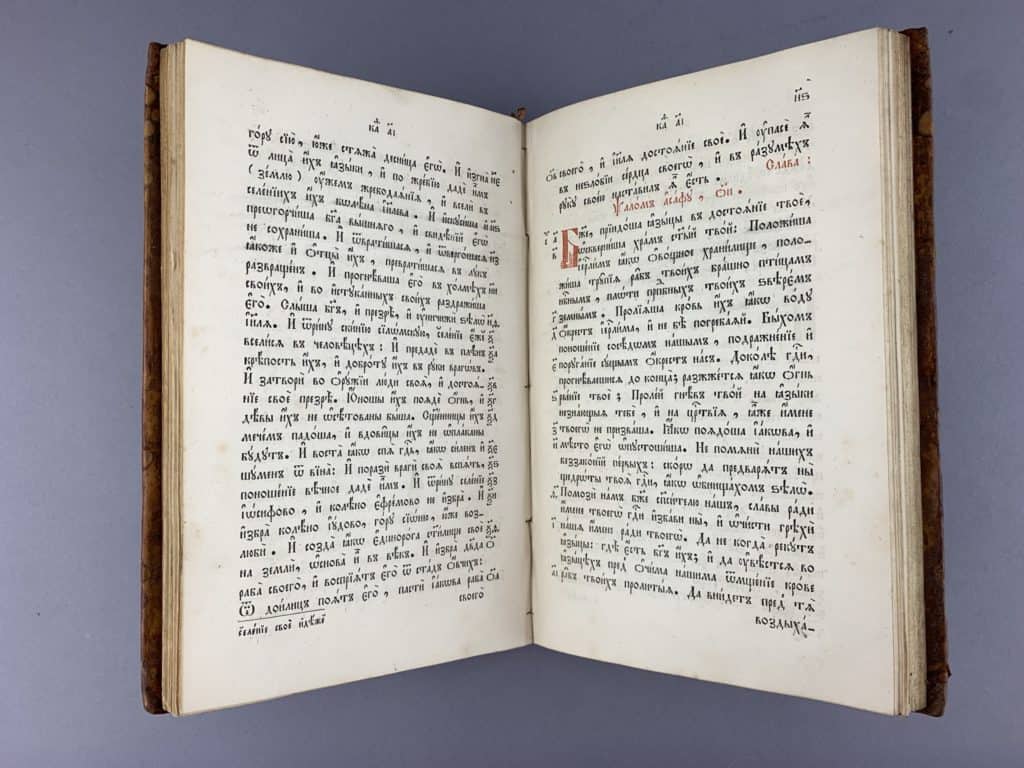

Closer detail: P︠S︡altirʹ. (Bible. Psalms.) Moskva: Synodalbhaia Tyts, 1851. Russian. [x-Collection, BS1425 C4 1851] University of Iowa Special Collections & Archives

-Text by Dr. Anna Barker for From Revolutionary Outcast to a Man of God: Dostoevsky at 200, University of Iowa Libraries Main Library Gallery.