Documenting Dada / Disseminating Dada is an exhibition featuring items from the University of Iowa Libraries’ International Dada Archive, the world’s most comprehensive collection of material related to the Dada movement.

From 1916 to 1923, a new kind of artistic movement swept Europe and America. Its very name, “DADA,” was notably missing the obligatory “ism,” distinguishing it from the long line of avant-gardes that had determined the preceding century of art history.

More than a mere art movement, Dada claimed a broader role as an agent of cultural, social, and political change. Its proponents wanted to affect all aspects of Western civilization, to take part in the revolutionary changes unfolding as inevitable results of the chaos of World War I.

The Dada movement was perhaps the single most decisive influence on the development of twentieth-century art, and its innovations are so pervasive as to be virtually taken for granted today.

This exhibition highlights Dada’s printed output, which documents the ephemeral aspects of the movement and shows how the dadaists used their publications to spread the movement beyond its origins in Zurich.

Download the Dada Guide Booklet (PDF)

Examples of items in this exhibition

A few of the items featured in Documenting Dada / Disseminating Dada are pictured below, including peeks inside select publications to show interior pages not on display.

| Exhibit item | Description |

|---|---|

|

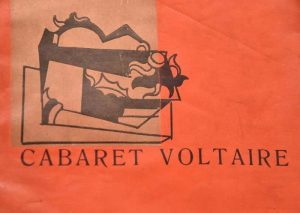

Cabaret Voltaire (ITEM 1 in the exhibition) was the title of the first Dada publication. Edited by Hugo Ball and published in May 1916, its innocent subtitle — A Collection of Artistic and Literary Contributions — understated the radical nature of some of its contents, such as the “simultaneous poem” read in three languages by the German Richard Huelsenbeck and the Romanians Marcel Janco and Tristan Tzara. This is a detail of the publication’s cover. |

|

| The pages of Cabaret Voltaire feature “a collection of Artistic and Literary Contributions,” including this early print by Pablo Picasso. | |

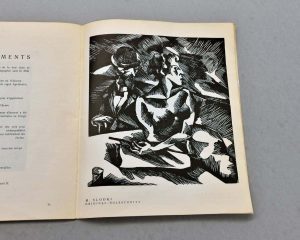

| Another page of Cabaret Voltaire shows this print by Marcel Slodki. | |

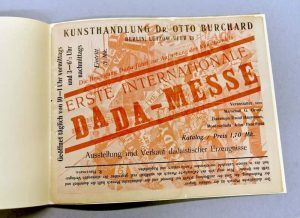

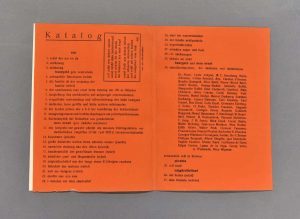

| Catalog for the First International Dada Fair (ITEM 47). | |

|

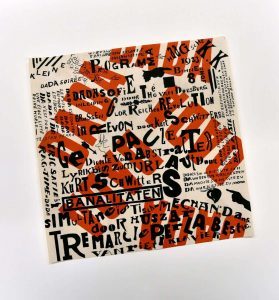

Dada in the Netherlands was largely the project of Theo van Doesburg, leader of the abstract-constructivist movement in art and architecture known as “De Stijl.” Using the Dada pseudonym “I.K. Bonset,” Doesburg organized a series of events in cities and towns around the country, some in collaboration with Kurt Schwitters. One of these was the 1923 Kleine Dada soirée in the Hague, for which Schwitters designed the poster (ITEM 35), considered one of the masterpieces of Dada design. |

|

|

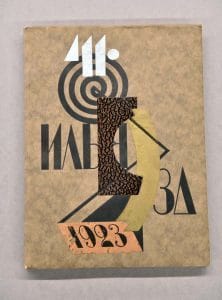

In Russia, experimental writers developed a language for sound poetry they called “zaoum.” The Georgian- Russian writer Iliazd (Ilia Zdanevich), who became involved with the Paris dadaists, published a book-length dramatic poem in “zaoum,” Lidantiu faram (ITEM 59). This is an image of the cover handcrafted with gold foil. |

|

|

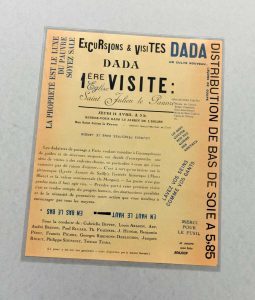

A guided tour of the little-known church of Saint Julien le Pauvre was advertised as the first of several Excursions et visites Dada (ITEM 14), tours of “places that have no reason to exist.” |

|

|

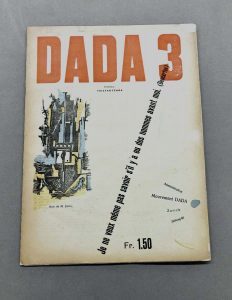

Tristan Tzara edited the review Dada beginning in 1917 in Zurich. The first two issues featured a consistent, relatively conventional format, but beginning with issue number 3 (pictured here, ITEM 4 in the exhibition), the format varies radically with each issue. Numbers 3 and 4/5 give evidence of Tzara’s desire (as the self-proclaimed leader of the movement) to take Dada to Paris, the capital of the artistic world. |

|

|

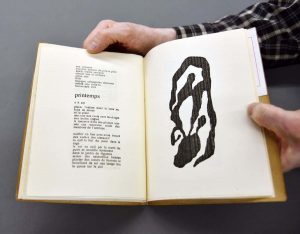

A publication in the “Collection Dada,” Tzara’s 1918 Vingt-cinq poèmes (ITEM 8) featured woodcuts by the Alsatian poet and artist Hans (Jean) Arp. Born in what was then Germany, Arp became French after the war, when Germany lost Alsace to France. The image here shows an inside page of the publication. |

|

|

Dada pointedly printed contributions in several languages from both sides of the Great War— including German. But with the war barely over, French censorship prevented the importing of any German literature. Tzara’s solution was to issue alternative editions, switching French for German content in the last two numbers published in Zurich. We see this tactic in the two versions of no. 4/5 (“Anthologie Dada”) (ITEM 6). |

|

| Detail from cover of Tzara’s Dada no. 2 (ITEM 2). | |

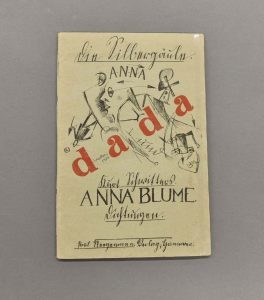

| Anna Blume Dichtungen (ITEM 55) is a collection of writings by Kurt Schwitters, the founder of Merz, Hanover’s version of Dada. | |

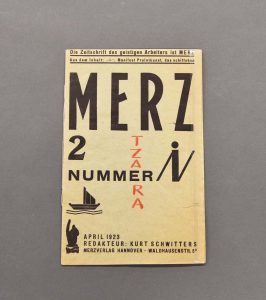

| The University of Iowa Libraries’ copies of Merz no. 1 and 2 came from the personal collection of Tristan Tzara. The cover of no. 2 (ITEM 52) bears a hand-lettered inscription to Tzara from the editor. | |

| The most notorious of the Dada events in Cologne was the exhibition Dada-Vorfrühling (ITEM 31) (a title suggesting the European revolutionary movements of 1848), held in the courtyard of a brewery and accessible only through the men’s restroom. | |

|

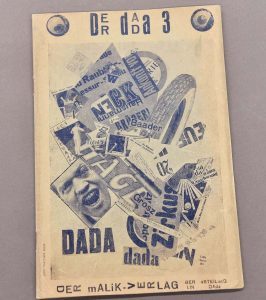

Wieland Herzfelde’s Malik-Verlag began life as the publishing arm of Berlin Dada, issuing the three numbers of the review Der Dada (the cover of No. 3 is shown here, ITEM 38) from 1919 to 1920. These issues display some of the distinctive artistic strategies of Dada in Berlin: fragmented language and phonetic poetry, politically charged photomontage, and tongue-in-cheek political organizations, such as the office for the establishment of separatist states announced in no. 1. |

|

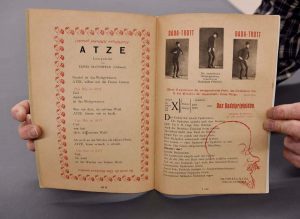

| Inside page of Der Dada no. 3 (ITEM 38). | |

|

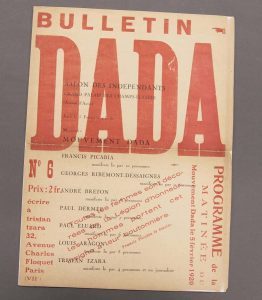

In Paris, Tzara published two more numbers of his review Dada (one of them, ITEM 24, is shown here), both in connection with Dada performances in early 1920. |

|

|

As in Zurich and Berlin, Dada in Paris was characterized more by transient events and actions than by concrete productions like books and paintings. A series of small one-man exhibitions, including Exposition Dada Man Ray (ITEM 15), are documented by ephemeral catalog-brochures, announcements, and invitations. This item is particularly fragile, printed on thin paper with a shiny eggplant-colored reverse side. |

|

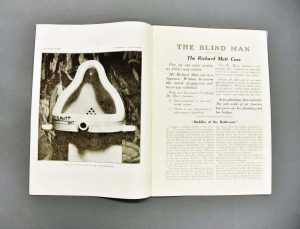

| One submission to the 1917 Independents Exhibition by an “R. Mutt” was a porcelain urinal displayed on its back and entitled Fountain. The directors rejected the piece, and Duchamp resigned in protest. The review The Blind Man had devoted its first issue to promoting the exhibition; the second issue (ITEM 11) was devoted to the “R. Mutt Affair” and pointedly featured an image of the offending sculpture taken by Stieglitz, the pioneer of artistic photography. Only later was it revealed that Duchamp himself had submitted the urinal, one of his many so-called “readymades” (found objects). | |

|

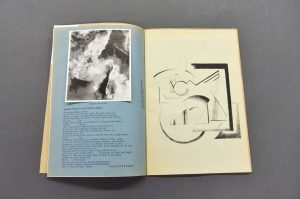

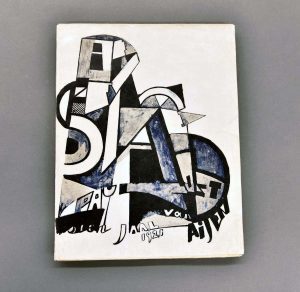

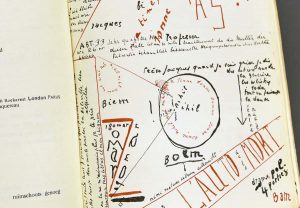

In bilingual Belgium, several French-language writers were tied to Paris Dada. On the Flemish side, Paul van Ostaijen had the closest connections to Dada. His epic multilingual visual poem Bezette stad (ITEM 58) reflects mixed reactions to the wartime German occupation among Flemish writers. Some felt a closer kinship to young German writers assigned to the occupation forces than to their French-speaking compatriots. Bezette stad seems to partake equally of Berlin and Paris Dada. |

|

| An inside page from Bezette stad (ITEM 58). |

Object list

- Cabaret Voltaire. Edited by Hugo Ball. Zurich, 1916.

- Dada no. 1. Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, July 1917.

- Dada no. 2. Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, December 1917.

- Dada no. 3 (international edition). Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, December 1918.

- Dada no. 4 / 5 (Anthologie Dada) (international edition). Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, May 1919.

- Dada no. 4 / 5 (Anthologie Dada) (French edition). Edited by Tristan Tzara. Zurich, May 1919.

- La Première Aventure céléste de Mr. Antipyrine. By Tristan Tzara; illustrated by Marcel Janco. Zurich, 1916.

- Vingt-cinq Poèmes. By Tristan Tzara; illustrated by Hans Arp. Zurich, 1918.

- 391 no. 8. Edited by Francis Picabia. Zurich, February 1919.

- 291 no. 2. Edited by Marius de Zayas, Agnes Meyer, Paul Haviland, and Alfred Stieglitz. New York, April 1915.

- The Blind Man no. 2. Edited by Henri-Pierre Roché, Beatrice Wood, and Marcel Duchamp. New York, May 1917.

- 391 no. 7. Edited by Francis Picabia. New York, August 1917.

- 391 no. 14. Edited by Francis Picabia. Paris, November 1920.

- Excursions et visites Dada. Paris, 1921.

- Une Bonne Nouvelle. (Invitation to opening of Exposition Dada Man Ray). Paris, 1921.

- Exposition Dada Max Ernst. Paris, 1921.

- [Papillon Dada: “Chaque spectateur est un intrigant”]. Zurich, 1919.

- [Papillon Dada: “Dada: Société Anonyme pour l’exploitation du vocabulaire”]. Zurich, 1919.

- Exposition Dada Francis Picabia. Paris, 1920.

- Exposition Dada Georges Ribemont Dessaignes. Paris, 1920.

- Exposition Dada Man Ray. Paris, 1921.

- [Papillon Dada: “La seule expression de l’homme moderne”]. Paris, 1920.

- [Papillon Dada: “Dada ne signifie rien”]. Zurich, 1919.

- Dada no. 6 (Bulletin Dada). Edited by Tristan Tzara. Paris, February 1920.

- Dada no. 7 (Dadaphone). Edited by Tristan Tzara. Paris, March 1920.

- Projecteur no. 1. Edited by Céline Arnauld. Paris, May 1920.

- Le Cœur à barbe. Edited by Tristan Tzara. Paris, April 1922.

- Cannibale no. 1. Edited by Francis Picabia. Paris, April 1920.

- Proverbe no. 3. Edited by Paul Éluard. Paris, April 1920.

- Die Schammade. Edited by Max Ernst and Johannes Baaargeld. Cologne, 1920.

- Dada Ausstellung: Dada-Vorfrühling. Cologne, 1920.

- Mécano red number. Edited by I.K. Bonset (Theo van Doesburg). Leiden, 1922.

- Anthologie-Bonset. By I.K. Bonset (Theo van Doesburg). Leiden, 1921.

- Wat is Dada? By Theo van Doesburg. The Hague, 1923.

- Kleine Dada Soirée: Programma. Poster by Theo van Doesburg and Kurt Schwitters. [The Hague?], 1922.

- Der Dada no. 1. Edited by Raoul Hausmann. Berlin, June 1919.

- Der Dada no. 2. Edited by Raoul Hausmann. Berlin, December 1919.

- Der Dada no. 3. Edited by George Grosz, John Heartfield, and Raoul Hausmann. Berlin, April 1920.

- Phantastische Gebete (second expanded edition). By Richard Huelsenbeck; illustrated by George Grosz. Berlin, 1920.

- Das Gesicht der herrschenden Klasse: 57 politische Zeichnungen (third expanded edition). By George Grosz. Berlin, 1921.

- Die Rote Woche: Roman. By Franz Jung; illustrated by George Grosz. Berlin, 1921.

- Tragigrotesken der Nacht: Träume. By Wieland Herzfelde; illustrated by George Grosz. Berlin, 1920.

- Schutzhaft: Erlebnisse vom 7. bis 20. März bei den deutschen Ordnungstruppen. By Wieland Herzfelde. Berlin, 1919.

- DaDa: Dadaistscher Fox-trot für Trottel und solche die es noch werden wollen. Music by Ober-DaDa Hajós (Karl Hajós); words by DaDaeda. Berlin, 1920.

- Dada-Enzyklopädie des Osiris. By Alfred Sauermann. Berlin, 1919.

- Die dadaistische Korruption. By Walter Petry. Berlin, 1920.

- Erste International Dada-Messe. Berlin, 1920.

- Dada Almanach. Edited by Richard Huelsenbeck. Berlin, 1920.

- En avant Dada: Eine Geschichte des Dadaismus. By Richard Huelsenbeck. Hanover, 1920.

- Dada siegt!: Eine Bilanz des Dadaismus. By Richard Huelsenbeck. Berlin, 1920.

- Merz no. 1 (Holland Dada). Edited by Kurt Schwitters. Hanover, January 1923.

- Merz no. 2 (Nummer i). Edited by Kurt Schwitters. Hanover, 1923.

- Merz no. 21 (Erstes Veilchenheft). By Kurt Schwitters. Hanover, 1931.

- Merz no. 24 (Ursonate). By Kurt Schwitters. Hanover, 1932.

- Anna Blume Dichtungen. By Kurt Schwitters. Hanover, 1919.

- Dada. By Shinkichi Takahashi. Tokyo, 1923.

- 75 HP. Edited by Ilarie Voronca and Victor Brauner. Bucharest, 1924.

- Bezette stad. By Paul van Ostaijen. Antwerp, 1921.

- Lidantiu faram. By Iliazd. Paris, 1921.

- Dadaizm: Kompiliatsiia. Berlin, 1922.

- Arte astratta. By Julius Evola. Rome, 1920.

- Garage. Music by E.L.T. Mesens; text by Philippe Soupault; cover by Man Ray. Brussels, 1926.

- Tre marcie per le bestie. By Vittorio Rieti. Bologna, 1922.

- Istočni greh: Misterij za bezbožne ljude čiste savesti. By Ljubomir Micić. Zagreb, 1920.

- Dada Artifacts. Exhibition catalog, University of Iowa Museum of Art. Iowa City, 1978.

- Dada Spectrum: The Dialectics of Revolt. Conference proceedings, University of Iowa Museum of Art. Edited by Stephen C. Foster and Rudo E. Kuenzli. Madison and Iowa City, 1979.

- Dada/Surrealism no. 10/11. Edited by Mary Ann Caws and Rudolf E. Kuenzli. Iowa City, 1982.

- Dada/Surrealism no. 12. Edited by Mary Ann Caws and Rudolf E. Kuenzli. Iowa City, 1983.

- Dada/Surrealism no. 14. Edited by Mary Ann Caws and Rudolf E. Kuenzli. Iowa City, 1985.

- Dada/Surrealism no. 15. Edited by Mary Ann Caws and Rudolf E. Kuenzli. Iowa City, 1986.

- New York Dada. Edited by Rudolf E. Kuenzli. New York, 1986.

- Dada and Surrealist Film. Edited by Rudolf E. Kuenzli. New York, 1987.

- Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century. Edited by Rudolf E. Kuenzli and Francis M. Naumann. Cambridge, 1989.

- Books at Iowa no. 39. Edited by Frank Paluka. Iowa City, 1983.

EXHIBITION CREDITS

DOCUMENTING DADA / DISSEMINATING DADA

is an exhibition drawn from the holdings of the International Dada Archive, Special Collections, the University of Iowa Libraries.

EXHIBITION CURATION

Timothy Shipe, Curator, International Dada Archive, UI Libraries Special Collections

PREPARATION & INSTALLATION

Giselle Simon & Bill Voss, UI Libraries Conservation Lab

FEATURED ARTWORK IN FRONT CASE

Kalmia Strong & John Engelbrecht, co-founders of Public Space One in Iowa City.

DESIGN

Heidi Wiren Bartlett, UI Libraries creative coordinator

EXHIBITION GUIDE TEXT

Timothy Shipe, UI Libraries Special Collections

EXHIBITION GUIDE EDITING, WEB SITE & PUBLICITY

Jennifer Masada, UI Libraries communications

PUBLIC PROGRAMMING COORDINATION

Timothy Shipe, UI Libraries Special Collections

FINANCIAL SUPPORT FOR THE EXHIBITION

Friends of the UI Libraries

FINANCIAL SUPPORT FOR PUBLIC PROGRAMMING

The journal Dada/Surrealism, the UI School of Library and Information Science – Newsome Lecture Fund, the UI International Writing Program, and the UI MFA Program in Literary Translation